When your child’s asthma inhaler suddenly looks different - smaller, lighter, maybe a different color - it’s easy to assume it’s the same medicine. But for kids, especially those on long-term medications, that small change can mean big risks. Generics make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., and insurers are pushing them hard to cut costs. But children aren’t small adults. Their bodies process drugs differently, and switching medications without careful planning can lead to serious health setbacks.

Why Switching Medications for Kids Is Riskier Than You Think

The FDA says a generic drug must contain the same active ingredient as the brand-name version and be within 80-125% of the original’s absorption rate. That sounds fine - until you realize that range allows for a 45% difference in how much medicine actually gets into the bloodstream. For adults taking blood pressure pills, that might not matter. For a child on seizure medication like phenytoin or a transplant drug like tacrolimus, even a 10% drop can trigger a seizure or organ rejection. A 2015 study of pediatric heart transplant patients found that after switching from brand-name Prograf to generic tacrolimus, blood levels dropped by an average of 14%. That’s not a rounding error - it’s a clinical red flag. The same issue shows up with asthma controllers, antidepressants, and even acid reflux drugs like omeprazole. In babies under 3 months, liver enzymes that break down these drugs aren’t fully developed. A generic version that works perfectly in a 10-year-old might be ineffective - or toxic - in a 6-month-old.What’s Really in the Pill? It’s Not Just the Active Ingredient

Many parents don’t realize that generics can have different fillers, dyes, or binders. These inactive ingredients don’t treat the illness, but they can trigger reactions in sensitive kids. One child might develop a rash from a dye used in one generic brand but not another. Another might gag on the flavor of a new liquid formulation, leading to missed doses. This matters most with chronic conditions. Kids with asthma, epilepsy, or ADHD need consistent, predictable dosing. A switch from one generic to another - even if both are labeled the same - can disrupt their routine. A 2020 study from PolicyLab found that after insurers switched asthma medications, caregiver confusion caused adherence to drop by 15-20%. That’s not because parents are careless. It’s because the new pill looks different, the inhaler has a new click, or the syrup tastes bitter. For a child who already struggles with daily meds, that’s enough to make them refuse.How Insurers Drive Switches - and Why It’s Not Always Safe

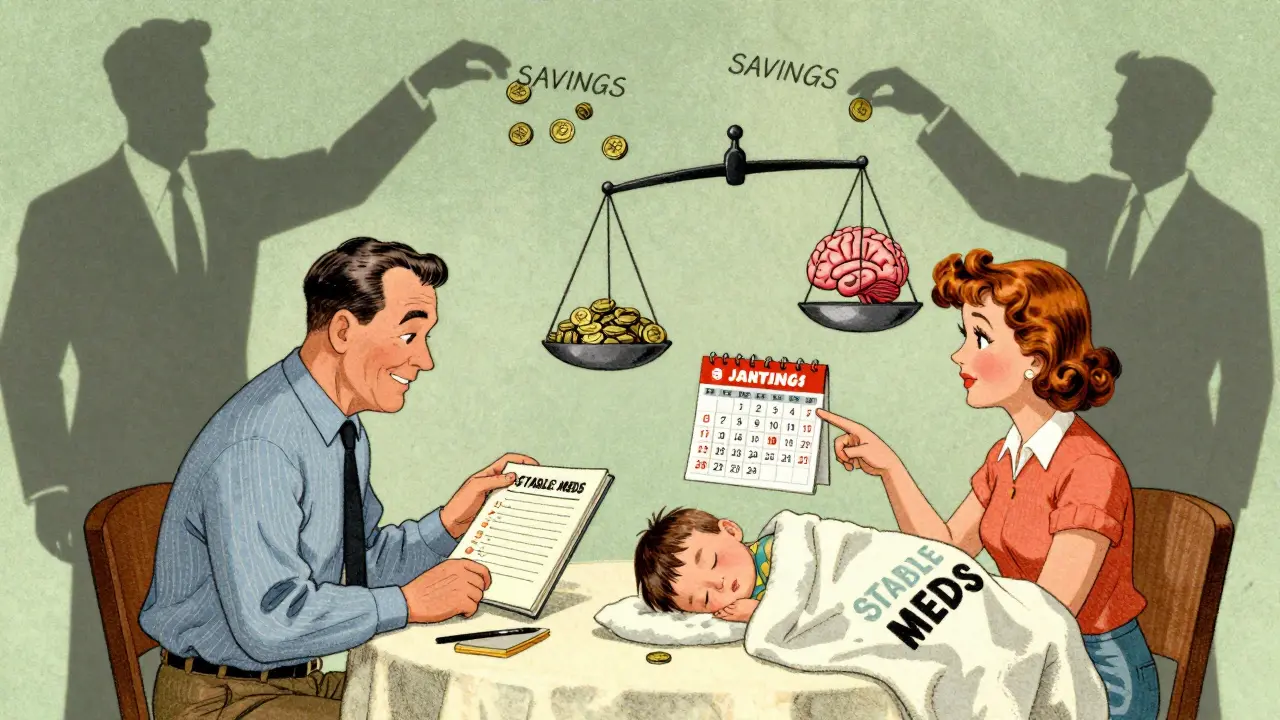

Most switches aren’t driven by doctors. They’re pushed by insurance companies trying to save money. This is called non-medical formulary switching. It means a child’s prescription gets changed not because it’s better, but because the insurer negotiated a lower price with a different manufacturer. In 2021, UnitedHealthcare changed formularies affecting 4.2 million children. One child might be on a stable brand-name inhaler for years, then suddenly get switched to a cheaper generic. Six months later, the insurer might switch again because another drug got a better deal. This rollercoaster is common. The Children’s Hospital Association reports families often face multiple switches in a single year - each one risking a flare-up, hospital visit, or missed school days.

State Laws Vary Wildly - And Most Don’t Protect Kids

There’s no national standard for switching pediatric meds. In 19 states, pharmacists can swap a brand-name drug for a generic without telling the parent. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get consent. In 31, they just have to notify - often with a tiny print note on the label that most parents never read. A 2009 study showed that states requiring consent had 25% fewer switches. That proves one thing: if families are asked before the change, they push back - and that protects kids. But most parents aren’t even told until they pick up the prescription. By then, it’s too late to ask the doctor if the switch is safe.What You Can Do to Protect Your Child

You don’t have to accept every switch. Here’s how to take control:- Ask your doctor: Is this switch medically necessary? Are there studies showing this generic works as well in children this age?

- Check the label: If the pill looks different, ask the pharmacist why. Write down the name of the manufacturer.

- Request a hold: If your child is stable on a medication, ask for a prior authorization to keep the brand-name version. Many insurers will approve it if you show it’s working.

- Track symptoms: Keep a simple log: sleep, energy, coughing, seizures, mood. Note any changes within 2 weeks of a switch.

- Speak up at the pharmacy: Say, “This is for a child with a chronic condition. I need to know if this is the same as before.”

What’s Changing - And What Might Help Soon

There’s growing pressure to fix this. The FDA’s 2022 Pediatric Formulation Initiative is pushing for better child-friendly versions of medicines. California passed a law in 2022 requiring Medicaid plans to include pediatric experts when making formulary changes. The American Academy of Pediatrics is finalizing new guidelines for prescribing generics in kids, due out late 2024. But right now, the system still treats children like miniature adults. Only 12% of generic approvals between 2010 and 2020 included any pediatric bioequivalence data. That means most switches are approved based on adult studies - even for babies.When to Say No - and When to Be Cautious

Some switches are low-risk. For antibiotics or short-term pain meds, generics are usually fine. But for these medications, be extra careful:- Anti-seizure drugs: Phenytoin, valproate, carbamazepine - even small changes can trigger seizures.

- Transplant drugs: Tacrolimus, cyclosporine - levels must be tightly controlled.

- Thyroid meds: Levothyroxine - small differences can affect growth and brain development.

- ADHD stimulants: Methylphenidate and amphetamines - changes can cause mood swings or loss of focus.

- Asthma controllers: Inhaled corticosteroids - if the device feels different, kids may not get the full dose.

Final Thought: Your Child’s Stability Matters More Than a Few Dollars

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system billions. That’s important. But when a child’s health is on the line, cost shouldn’t override safety. A 2023 meta-analysis found children with chronic conditions who switched medications had an 18% higher chance of being hospitalized. You know your child best. If something feels off after a switch - if they’re more tired, more irritable, or their condition seems to be slipping - speak up. Don’t wait. Ask for the old medication back. Document everything. And remember: a medicine that works isn’t just about the chemical name. It’s about how your child feels, breathes, sleeps, and learns. That’s worth fighting for.Are generic medications safe for children?

For many short-term or low-risk medications, yes. But for chronic conditions like epilepsy, asthma, or transplant care, generics can pose risks. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards were designed for adults, and children’s bodies process drugs differently. Small changes in absorption can lead to treatment failure or side effects. Always check with your pediatrician before switching.

Can a pharmacist switch my child’s medication without telling me?

In 19 states, yes - pharmacists can substitute a generic without your permission. In 7 states and Washington, D.C., they must get your consent. In most others, they only need to notify you - often with a small label note. Always ask the pharmacist before picking up a new prescription. If you’re unsure, call your doctor.

What should I do if my child’s medication looks different?

Don’t assume it’s the same. Check the name of the manufacturer and the active ingredient. Compare it to the previous version. If anything changes - color, shape, taste, or device design - ask the pharmacist why. Write down the new details and report any new symptoms to your child’s doctor within 1-2 weeks.

Which medications are most dangerous to switch in kids?

High-risk drugs include anti-seizure medicines (phenytoin, valproate), transplant drugs (tacrolimus), thyroid hormones (levothyroxine), ADHD stimulants (methylphenidate), and inhaled asthma controllers. These have narrow therapeutic windows - small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm. Avoid switching these without your doctor’s approval.

How can I keep my child on their current medication?

Ask your doctor to write a letter of medical necessity to your insurer. Explain why the current medication works for your child and why switching could be harmful. Many insurers will approve exceptions if you provide clear evidence. Keep records of your child’s symptoms and medication history - this strengthens your case.

14 Comments

My daughter’s asthma got worse after they switched her inhaler without telling us. We didn’t notice until she was in the ER. Now I check every single pill. Every. Single. One. I don’t trust the system anymore.

It’s not about being paranoid. It’s about survival.

They treat kids like cost centers, not humans.

This whole thing is a joke. Why are we even having this conversation? If it’s FDA-approved, it’s safe. End of story. People need to stop being dramatic about pills.

My kid takes generics for everything and never missed a beat.

Thank you for writing this with such care. As a pediatric nurse for 22 years, I’ve seen too many children destabilize after an unannounced switch. The inactive ingredients? They matter. A lot. One child developed a full-body rash from a dye in a generic omeprazole that wasn’t in the brand version. The family had no idea why. No one told them.

Parents need to be empowered. Pharmacists need training. Insurers need accountability.

I’m so glad the AAP is working on new guidelines. It’s long overdue.

It’s funny how we’ve turned medicine into a capitalist game of musical chairs. We optimize for profit, then wonder why kids are suffering. The body isn’t a spreadsheet. A child’s liver isn’t a line item. We’re not just saving pennies-we’re gambling with neurodevelopment, organ function, sleep, school performance.

Generics aren’t the enemy. The system is.

And yet, we keep voting with our wallets for the cheapest option. What does that say about us? 🤔

Let me tell you what actually happens in real life. I’m a single dad. My son’s on tacrolimus. We got switched to generic without warning. Two weeks later, his creatinine spiked. We rushed to the hospital. Turned out his blood levels dropped 22%.

Insurance called it a "formulary update." We called it a near-death experience.

I called my doctor. I got a letter of medical necessity. I faxed it. I emailed it. I followed up every day for three weeks. They finally approved the brand. Took six months of hell to get there.

Don’t wait for the system to protect your kid. Fight. Now. Document everything. And if they try to switch again? Push back harder.

My wife and I have been keeping a log since our daughter started on phenytoin. We track sleep, mood, seizure frequency, even how much she eats. We’ve had two switches. Both times, the new version made her lethargic. We caught it because we were watching.

Pharmacists don’t know your kid. They’re just scanning barcodes.

Always ask: "Is this the same as last time?"

And if they say "yes," ask again.

And then ask your doctor.

And then write it down.

And then do it again next month.

Because no one else will.

There is no evidence that generics are less effective in children. The FDA’s bioequivalence standards are robust. You are attributing anecdotal experiences to systemic failure without data. The real issue is poor compliance, not pharmaceutical substitution.

Stop fearmongering. This is not a crisis. It’s a marketing narrative fueled by brand-name manufacturers trying to protect their margins.

I just wanted to say thank you for sharing this. I’m a mom of a 4-year-old with epilepsy. We’ve been on the same brand since she was 8 months old. I never even knew switches could happen without consent until I read this.

I’m going to call my pharmacist tomorrow and ask for a written notice if they ever change anything. I’m also asking my neurologist to write a letter for our insurance.

Thank you for giving me the courage to speak up.

❤️

Listen, I get it. I’m a mom too. But you know what? We can’t let fear stop us from saving money. We’re not rich. We’re not even middle-class anymore. If the generic works for 9 out of 10 kids, why should we be the 1 in 10 who gets special treatment?

My kid’s on a generic ADHD med. She’s fine. Focused. Sleeping. No issues.

Maybe the problem isn’t the drug. Maybe it’s the anxiety around it.

So let me get this straight: you’re telling me that because a pill looks different, my kid might die? 😭

And the FDA is just… letting this happen?

And pharmacists are just… swapping it out like it’s a coupon?

And I’m supposed to just… keep trusting them?

…

Okay, I’m done. I’m moving to Canada.

My daughter’s on levothyroxine. We’ve had three switches in two years. Each time, she got more tired, more moody. We didn’t connect it until we started tracking.

Now I take a photo of every pill before I give it to her. I keep a Google Sheet. I email the pharmacy every time. I’ve become the annoying mom.

And you know what? I don’t care.

She’s alive. She’s thriving. And I’d rather be annoying than sorry.

📸💊📊

Just wanted to add-my son’s on an inhaler. The new one had a different click sound. He stopped using it for three weeks because he thought it was broken. He didn’t say anything. He just… didn’t use it.

Turns out, it wasn’t broken. Just different.

He’s 7. He didn’t know how to ask.

Now I test every new inhaler with him before he leaves the pharmacy. We practice the click together.

It’s not about the drug. It’s about the experience.

It is, of course, entirely predictable that in a society where profit is the supreme value, the most vulnerable-children, the elderly, the chronically ill-will be the first to be sacrificed on the altar of efficiency. The FDA’s standards were never designed for pediatric physiology. This is not negligence. It is systemic malice cloaked in bureaucratic language.

When a child’s life becomes a line item in an actuarial table, we have ceased to be a civilization.

We are merely a market.

You think it’s just about the pill? Try explaining to your 5-year-old why the medicine that made her stop coughing now makes her cry for hours. She doesn’t understand "bioequivalence." She just knows it doesn’t feel right.

And when you can’t afford to fight the insurance company? You give it to her anyway.

And then you cry in the bathroom.

And then you do it again next month.

That’s parenting in America now.

Write a comment