When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: is this really the same as the brand-name version you used to pay more for? The answer isn’t just "yes" - it’s backed by strict science, rigorous testing, and a regulatory system designed to make sure you get the exact same effect, every time. That system is called bioequivalence, and it’s the backbone of how the FDA approves generic drugs.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

Bioequivalence isn’t about matching the color, shape, or price of a drug. It’s about matching how your body absorbs and uses the active ingredient. The FDA defines it simply: there must be no significant difference in the rate and extent to which the drug reaches its target in your body. In plain terms, if you take a generic version of a drug, it should produce the same blood levels over time as the brand-name version - no more, no less.

This isn’t a guess. It’s measured. Every generic drug must prove it delivers the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same speed as the original. That’s how the FDA ensures safety and effectiveness without forcing manufacturers to repeat every clinical trial ever done on the brand-name drug.

The Science Behind the Test

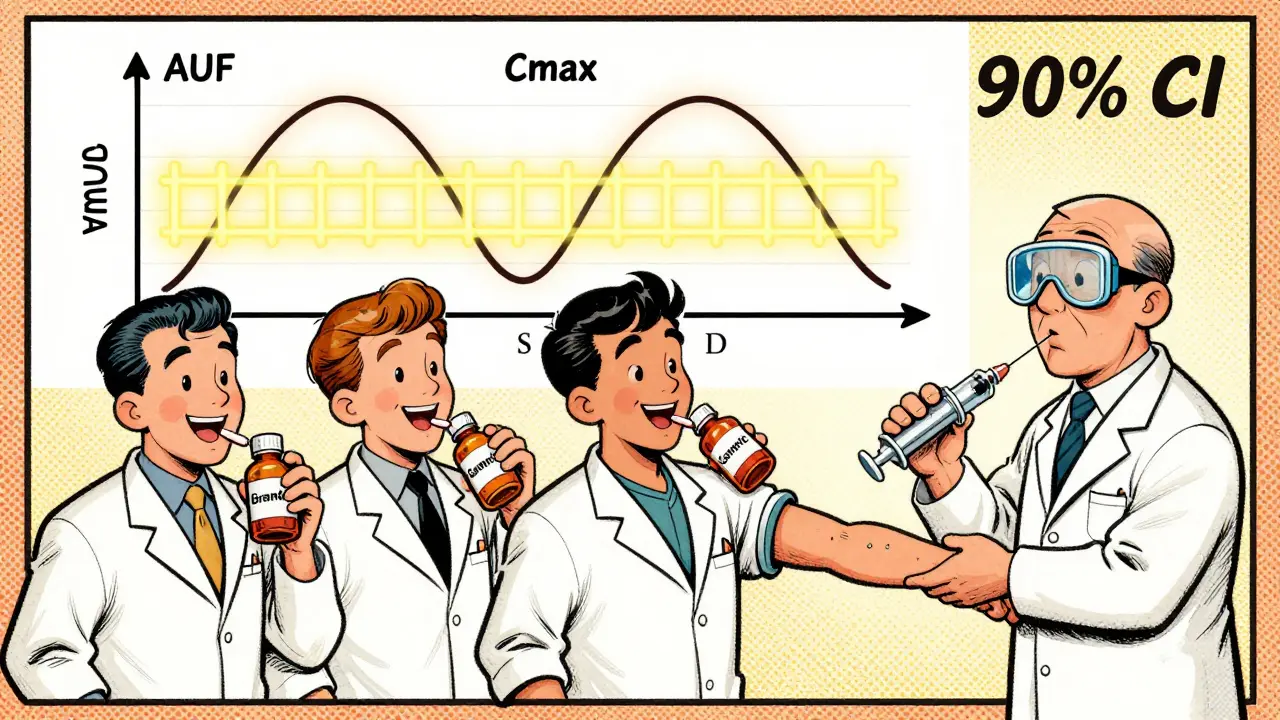

To prove bioequivalence, companies run studies with healthy volunteers - usually between 24 and 36 people. These aren’t patients with the condition the drug treats. They’re healthy because researchers need to measure how the body handles the drug without interference from disease.

The study is a crossover design: each volunteer takes both the brand-name drug and the generic version at different times, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken over hours to track how the drug moves through the body. Two key numbers are calculated:

- Cmax - the highest concentration of the drug in the blood.

- AUC - the total exposure over time, measured as the area under the concentration curve.

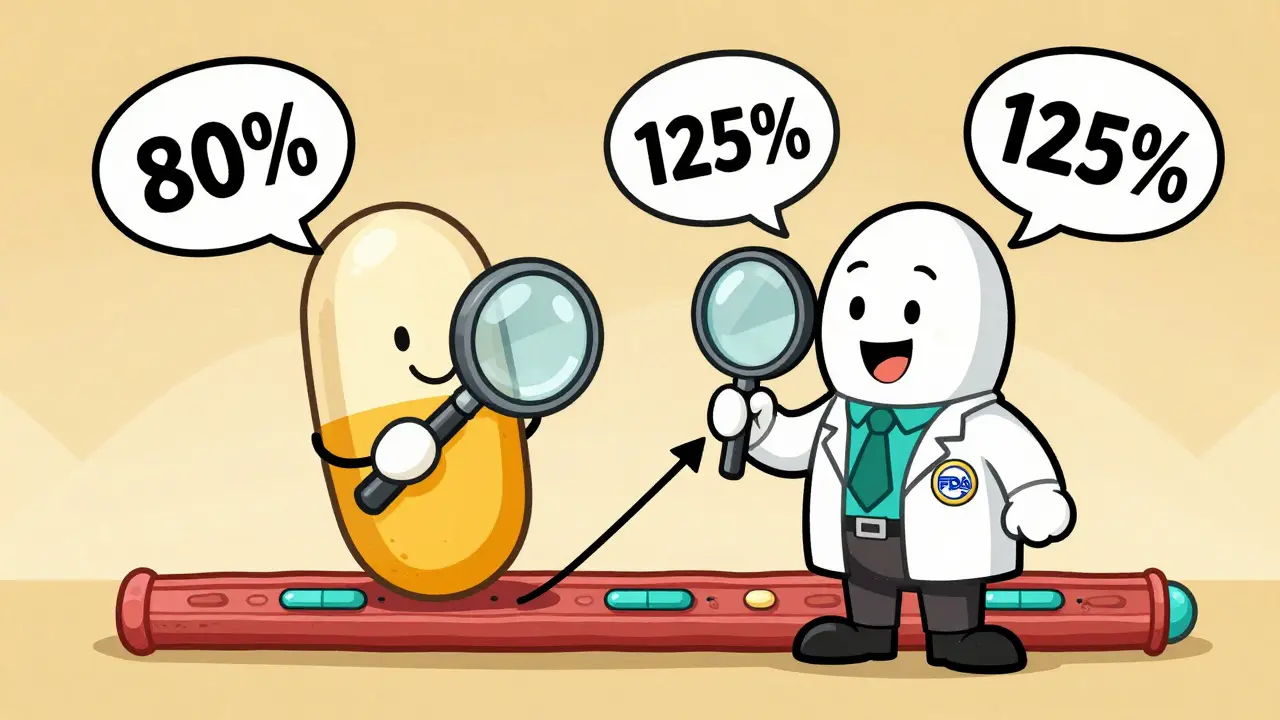

These aren’t just averages. The FDA looks at the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the ratio between the generic and the brand-name drug. For both Cmax and AUC, that interval must fall between 80% and 125%.

Let’s say the brand-name drug gives an average AUC of 100 units. The generic must show an AUC between 80 and 125 units. If the generic’s average is 93, and the 90% CI ranges from 84 to 110, it passes. But if the average is 116 and the CI goes up to 130, it fails - even if the average looks close. The entire range must fit inside the 80-125% window.

Common Misconceptions

Many people think the 80-125% range means the generic can contain anywhere from 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. The active ingredient amount in the tablet is tightly controlled - usually within 5% of the brand-name drug. The 80-125% rule applies only to how your body absorbs the drug, not how much is in the pill.

Think of it like this: two identical cars with the same engine size. One has a slightly different air filter. The car might accelerate a little slower or faster. But if both reach the same top speed and cover the same distance on a gallon of gas, they’re effectively the same. Bioequivalence is about performance, not parts.

Even some healthcare professionals get this wrong. A 2015 study found doctors were misinformed, thinking generics could contain 20% less or 25% more active ingredient. That’s not true. The FDA’s system is designed to prevent that kind of variation.

Pharmaceutical Equivalence Comes First

Before bioequivalence is even tested, the generic must meet pharmaceutical equivalence. That means:

- Same active ingredient

- Same strength

- Same dosage form (pill, injection, cream)

- Same route of administration (oral, topical, etc.)

- Same quality standards (purity, stability, dissolution)

If a generic doesn’t match the brand on these basics, it doesn’t even get to the bioequivalence stage. The FDA checks this with lab tests and manufacturing inspections.

What About Complex Drugs?

Not all drugs are created equal. For drugs that act locally - like inhalers, eye drops, or topical creams - the medicine doesn’t need to enter the bloodstream. In those cases, the FDA accepts in vitro testing: lab-based measurements of how the drug releases from the product. For example, an asthma inhaler might be tested by how much drug it sprays out and how fine the particles are.

But for drugs meant to work systemically - like antibiotics, blood pressure pills, or antidepressants - the drug must enter the bloodstream. That means in vivo studies with human volunteers are required.

Some drugs are trickier. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) - where even small changes can cause toxicity or treatment failure - include warfarin, lithium, and some anti-seizure meds. The FDA doesn’t change the 80-125% rule for these, but it requires more data. Studies often involve more participants, multiple dosing periods, and sometimes even testing in patients, not just healthy volunteers.

The Approval Process

Generic manufacturers submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This isn’t a shortcut - it’s a science-based path. The FDA reviews every study, every batch, every manufacturing detail. The average review time is 10 to 12 months. About 65% of ANDAs get approved on the first try. The rest get deficiency letters - often because the bioequivalence data didn’t meet the 80-125% standard, or the manufacturing process wasn’t consistent.

Since 2021, the FDA requires companies to submit all bioequivalence studies they ran - not just the successful ones. This increases transparency. If a company ran five studies and only one passed, the FDA still sees the other four. That helps catch patterns: maybe the formulation works in one lab but fails in another. That’s a red flag.

Why This Matters

Generics make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they cost only about 20% of what brand-name drugs do. Between 2010 and 2019, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion. That’s not just a number - it’s millions of people who can afford their meds.

The FDA’s bioequivalence standard is why you can trust a generic. It’s not cheaper because it’s worse. It’s cheaper because the science already exists. The generic company doesn’t have to repeat expensive trials - they just have to prove they can deliver the same result.

Every time you take a generic, you’re benefiting from a system built on precise measurements, strict rules, and decades of regulatory science. The FDA doesn’t approve generics because they’re affordable. They’re affordable because they meet the same standard as the brand.

What’s Next?

The FDA is working on new ways to evaluate complex generics - like topical creams that don’t absorb the same way for everyone, or inhalers with tricky delivery systems. Modeling and simulation tools are being tested to reduce the need for human trials in some cases. But the core rule remains: if a drug is meant to work in your bloodstream, it must prove it behaves the same as the original.

For now, the 80-125% confidence interval rule stands as one of the most reliable, science-backed systems in modern medicine. It’s not perfect - but it’s the best we have. And it works.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same strict standards as brand-name drugs. They must contain the same active ingredient, in the same amount, and deliver it to your body at the same rate and extent. Bioequivalence studies prove this. Millions of people use generics every day with the same results as the brand-name versions.

Can a generic drug have a different inactive ingredient?

Yes. Generic drugs can have different fillers, dyes, or preservatives - as long as they don’t affect how the active ingredient is absorbed. These inactive ingredients don’t change the drug’s effect. But if you have allergies (like to certain dyes or lactose), you should check the label. The active ingredient remains identical.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Sometimes, it’s psychological. People expect generics to be less effective because they cost less. In rare cases, switching between different generic versions (from different manufacturers) can cause small changes in how a drug is absorbed - especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs. But this isn’t because generics are inferior. It’s because even small differences in manufacturing can affect dissolution. The FDA monitors this closely, and doctors can adjust if needed.

Do all generic drugs go through the same testing?

Yes. All generics must prove bioequivalence using the same FDA standards. The method may vary slightly - for example, a cream might be tested in a lab, while a pill needs human trials - but the goal is always the same: to show the drug performs identically to the brand-name version.

What happens if a generic fails bioequivalence testing?

The FDA rejects the application. The manufacturer can revise the formulation, run new studies, and resubmit. Many companies do this - sometimes multiple times - before approval. The FDA doesn’t approve a generic just because it’s cheaper. It approves it only when the science proves it’s equivalent.

1 Comments

I love how the FDA has this system in place!!! It’s so reassuring to know that my $4 generic blood pressure pill is doing the exact same thing as the $400 brand-name one. I used to be skeptical, but now I’m all in. 🙌💯

Write a comment