EMA vs FDA Labeling Comparison Tool

Compare Labeling Differences

Select a labeling aspect to see how the EMA and FDA differ in their approaches to drug labeling.

Comparison Results

Select a category to see differences between EMA and FDA drug labeling.

When a new drug hits the market in the U.S. or Europe, the label you read isn’t just a piece of paper-it’s the result of two very different regulatory systems working in parallel. The EMA (European Medicines Agency) and the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) both approve life-saving medicines, but how they write the instructions, warnings, and uses can vary dramatically. For patients, doctors, and pharmaceutical companies, these differences aren’t just technical-they affect access, safety, cost, and even treatment outcomes.

What’s on the Label? EMA’s SmPC vs FDA’s PI

In Europe, drug labels are called Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). In the U.S., they’re called Prescribing Information (PI). At first glance, they look similar: both list dosage, side effects, contraindications, and clinical data. But dig deeper, and the differences become clear.

The EMA requires the SmPC to be written for healthcare professionals, with a structured format that includes detailed pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and clinical trial data. The FDA’s PI is also professional-focused, but tends to be more concise, prioritizing actionable clinical guidance over exhaustive data. A 2020 study analyzing 12 vaccines approved by both agencies found almost no alignment in how the same clinical evidence was presented. One vaccine’s label in the U.S. might say “not recommended for pregnant women,” while the European version simply states “use with caution,” based on the same data.

Why? Because the EMA and FDA interpret evidence differently. Even when given identical clinical trial results, they often reach different conclusions about what the data proves. In one analysis of 21 drugs, over half the labeling differences came from the agencies disagreeing on whether the evidence was strong enough to support a particular use. That means a drug approved for the same condition in both regions might have completely different instructions on how it should be used.

Who Gets to Say What? Patient-Reported Outcomes

One of the biggest gaps between the two agencies is how they handle patient-reported outcomes (PROs)-things like pain levels, fatigue, or quality of life improvements that patients themselves describe.

Between 2006 and 2010, a study by RTI Health Solutions found that 47% of drugs approved by the EMA included at least one PRO claim on the label. The FDA? Only 19%. And only 4 out of 75 drugs had identical PRO claims approved by both. For example, if a drug improved patients’ ability to walk without pain, the EMA might allow the label to say “improves functional mobility,” while the FDA might only accept “reduces pain scores.”

This isn’t about data quality-it’s about philosophy. The EMA is more open to including patient experience as part of the clinical benefit. The FDA, historically, has been more cautious, requiring stricter validation before allowing such claims. That means a drug might be marketed with broader benefits in Europe, while its U.S. label is more limited, even if the underlying data is the same.

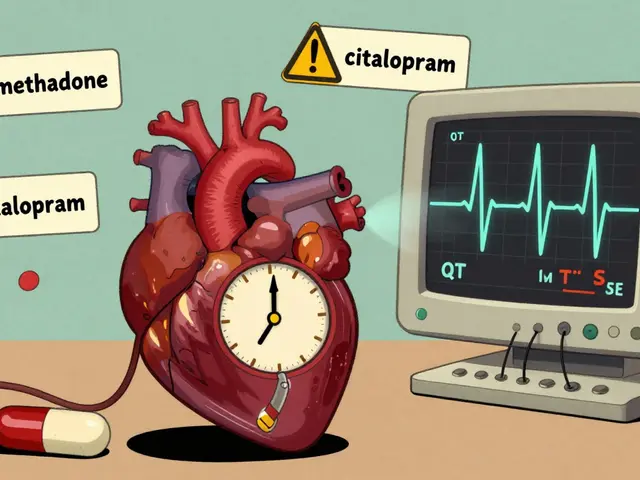

Pregnancy, Lactation, and Risk: Different Words, Different Messages

When it comes to pregnancy and breastfeeding, the labeling differences are stark-and sometimes life-changing.

A 2023 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics looked at how the two agencies labeled drugs with human pregnancy data. For two specific medications, the FDA issued warnings that discouraged use during pregnancy, while the EMA used its standard, more neutral language. In one case, the FDA label said “avoid use in pregnancy,” while the EMA said “use only if benefit justifies potential risk.”

That difference isn’t just wording. It affects how doctors prescribe and how patients decide. In the U.S., a more cautious label can lead to under-treatment. In Europe, a more balanced message might allow more women to access necessary care. The EMA tends to frame risk as a continuum. The FDA often frames it as a binary: safe or unsafe.

Language: 24 Versions vs One

Here’s a practical nightmare for drugmakers: the EMA requires every single drug label to be translated into all 24 official languages of the European Union. That includes everything from Czech to Maltese. The FDA? Only English.

That one difference adds 15-20% to the cost of bringing a drug to market in Europe, according to Mabion (2023). It’s not just translation-it’s formatting, review, regulatory submission, and verification for each language. A company submitting to the EMA must manage 24 separate versions of the same document, each subject to national authority review. The FDA? One submission. One review. One final version.

And it’s not just about cost. It’s about speed. A drug approved in the U.S. might hit shelves in 12 months. In the EU, it can take 18 months or more-partly because of the language burden. Companies often delay EU launch until after U.S. approval, just to manage the workload.

Risk Management: REMS vs RMP

When a drug has serious risks-like liver damage or birth defects-the agencies don’t just warn users. They enforce controls.

The FDA uses Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). These are strict, legally binding programs. For some drugs, REMS require that only one pharmacy distributor can supply the drug, or that doctors complete mandatory training before prescribing. Think of it like a locked box around the drug.

The EMA uses Risk Management Plans (RMPs). These are more flexible. They outline risks and mitigation strategies, but don’t mandate specific systems. Companies have freedom in how they implement them-through educational materials, monitoring programs, or pharmacist alerts. No single distributor. No mandatory training. Just a plan that’s reviewed and updated.

That means a drug with a REMS in the U.S. might be available over the counter in parts of Europe-or through regular pharmacies, without special restrictions. It also means companies have to build two separate systems: one for the U.S., one for Europe. That doubles the compliance burden.

Approval Speed and Evidence Standards

Who approves drugs faster? The EMA. In 2019, the EMA approved 92% of drugs on the first review cycle. The FDA approved only 85%. Why? Because the FDA is more likely to say “no” the first time-13% of applications get initial nonapproval, compared to just 3% at the EMA.

But here’s the twist: the FDA’s “no” isn’t always about safety. It’s often about evidence. The FDA wants more complete data before approving. The EMA is more willing to approve based on promising early data, especially for rare diseases. In fact, the EMA has a special “exceptional circumstances” pathway for ultra-rare conditions where full clinical trials aren’t possible. The FDA doesn’t have an equivalent. So a drug approved for an ultra-rare cancer in Europe might not get approved in the U.S. at all-or might require years of additional studies.

Why This Matters for Patients and Doctors

Imagine a patient on a drug approved in the U.S. travels to Germany. Their doctor there sees a different label. The dosage might be different. The warning might be weaker. The approved use might not even match.

Or imagine a doctor in London prescribing a drug based on the EMA label, only to find out the FDA label says “avoid in kidney disease,” while the EMA says “use with monitoring.” Which one do they follow? Neither is wrong. But they’re not the same.

For patients, this can mean confusion, delays, or even missed treatment. For doctors, it means double-checking sources, cross-referencing guidelines, and sometimes prescribing off-label because the local label doesn’t reflect the best evidence.

The Bottom Line: Harmonization Isn’t Happening-But It’s Getting Smarter

There’s been decades of effort to harmonize drug labeling through the ICH. But studies show little progress. As Dr. Yurim Seo put it: “No pattern was observed in the number of labeling elements harmonized over time.”

That doesn’t mean the agencies are working at cross-purposes. They share data. They hold joint meetings. They’ve signed confidentiality agreements. But their legal frameworks are too different to merge. The EMA is a network of national regulators. The FDA is a single federal agency with its own legal authority. Their cultures, risk tolerances, and priorities are different.

For pharmaceutical companies, the message is clear: don’t assume approval in one region means approval in the other. You need separate strategies, separate teams, and separate documentation. Companies now spend 30% more time preparing dual submissions than single ones. Many have built dedicated regulatory intelligence teams just to track these differences.

For patients and providers, the takeaway is simple: always check the label for your region. A drug isn’t just a drug. It’s a set of instructions shaped by where it was approved-and that matters.

Why do EMA and FDA labels differ even when the clinical data is the same?

Because the two agencies interpret evidence differently. The FDA often requires stronger proof of benefit before approving a use, while the EMA is more willing to approve based on promising data, especially for rare diseases. Even with identical clinical trials, they can reach different conclusions about what the data means-leading to different warnings, dosages, or approved uses.

Does the FDA accept drug labels in languages other than English?

No. The FDA only accepts submissions and labeling in English. All drug labels approved in the U.S. must be written and reviewed in English. This is one of the biggest contrasts with the EMA, which requires labels in all 24 official EU languages, significantly increasing the cost and complexity of approval.

Can a drug have different approved uses in the U.S. and Europe?

Yes. It’s common. For example, a drug might be approved for a specific type of cancer in the U.S. but not in Europe, or vice versa. Differences in how each agency weighs clinical evidence, especially around surrogate endpoints or patient-reported outcomes, lead to different approved indications-even for the same drug.

Why does the EMA allow more patient-reported outcome claims on labels?

The EMA has a broader definition of clinical benefit that includes how patients feel and function-not just lab results or survival rates. The FDA historically required stricter validation for these claims, though it has become more open in recent years. Still, the EMA approves PRO claims at more than double the rate of the FDA.

Which agency is faster to approve new drugs?

The EMA has a higher first-cycle approval rate (92%) compared to the FDA (85%). The FDA is more likely to request additional data before approval, which can delay decisions. However, once approved, FDA labels often come with fewer post-marketing requirements, while EMA approvals may require ongoing monitoring through Risk Management Plans.

Do drug companies need to create two separate labels for the U.S. and EU?

Yes. Due to differences in language requirements, risk management rules, approved indications, and formatting standards, companies must create and maintain separate labels for the U.S. and EU markets. This increases development time and cost by up to 30% compared to submitting to a single agency.

1 Comments

So the FDA just says 'avoid pregnancy' and EMA says 'use if benefit > risk'? That's wild. One's a scare tactic, the other's a risk-benefit chat. Guess which one lets more women get treated?

Write a comment