Immunosuppressant Selection Tool

| Side Effect | Recommended | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Renal Toxicity | ||

| Neurotoxicity | ||

| Infection Risk | ||

| Metabolic Effects | ||

| Cost (UK/£/month) |

When a transplant patient needs to keep their new organ from being rejected, the choice of immunosuppressant can feel like a high‑stakes gamble. Neoral (the brand name for cyclosporine) has been a mainstay for decades, but newer drugs promise fewer side‑effects or simpler dosing. This guide breaks down how Neoral works, lines it up against the most common alternatives, and gives you a practical checklist for deciding which drug fits a specific clinical picture.

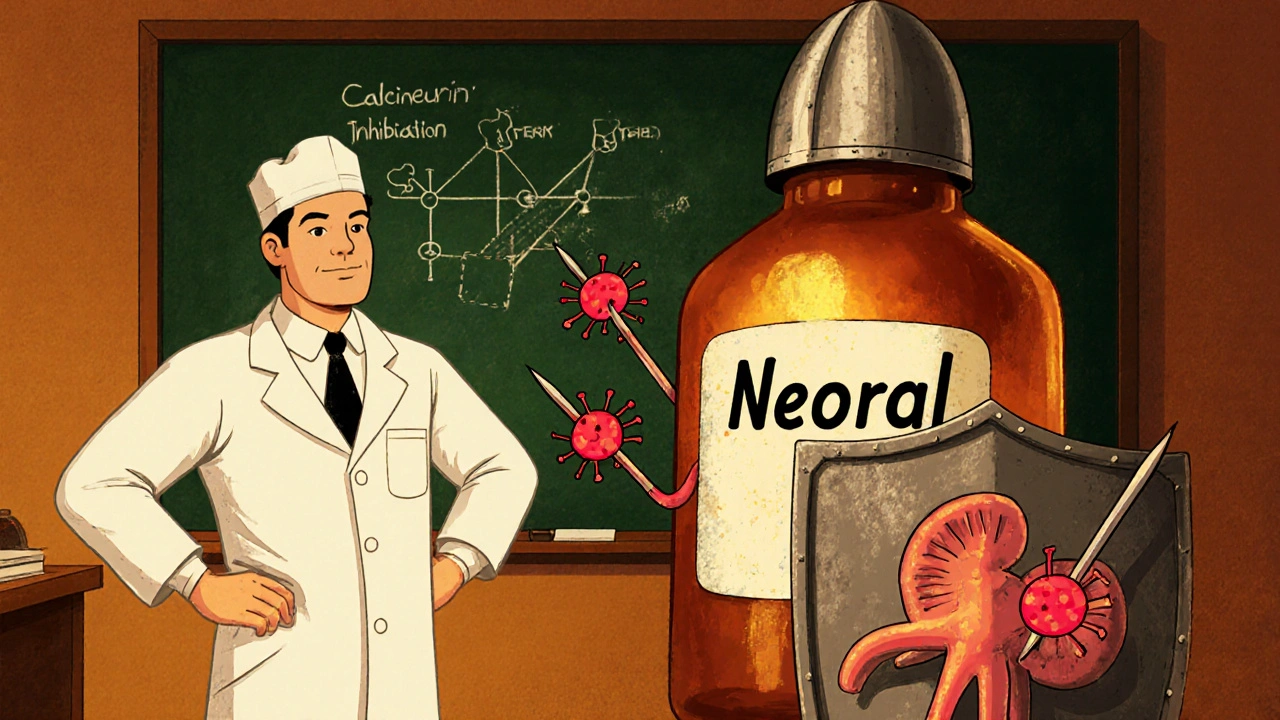

What is Neoral (Cyclosporine) and how does it work?

Neoral is a calcineurin inhibitor that suppresses T‑cell activation by blocking interleukin‑2 production. It was first approved in the early 1980s and quickly became the go‑to oral agent for kidney, liver and heart transplants.

Neoral binds to cyclophilin, forming a complex that inhibits the phosphatase activity of calcineurin. Without calcineurin, the transcription factor NFAT stays in the cytoplasm, so T‑cells can’t fire the genes that trigger an immune attack on the graft.

The drug is taken twice daily, with food to improve absorption. Because its bioavailability varies a lot between patients, doctors often use therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) to keep blood levels in the target window of 100‑200 ng/mL for most adult transplant protocols.

Key alternatives to Neoral

Over the past two decades several other immunosuppressants have entered the market. Each one hits a different step in the immune cascade, which translates into distinct side‑effect profiles and dosing needs.

- Mycophenolate mofetil - an antiproliferative that blocks guanine synthesis in lymphocytes.

- Tacrolimus - another calcineurin inhibitor, often marketed as Prograf.

- Sirolimus (rapamycin) - an mTOR inhibitor that prevents cell cycle progression in T‑cells.

- Azathioprine - a purine analogue that interferes with DNA synthesis in rapidly dividing cells.

These agents are usually combined with low‑dose steroids, but many protocols now aim for steroid‑free regimens by relying heavily on the newer drugs.

Side‑effect snapshot: Neoral vs the competition

Every immunosuppressant carries a trade‑off between efficacy and toxicity. Below is a quick visual of the most common adverse events, based on pooled data from the United Kingdom Transplant Registry (2023‑2024).

| Drug | Renal toxicity | Neuro‑toxicity | Infection risk | Metabolic effects | Cost (UK, per month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoral (Cyclosporine) | High - dose‑related nephrotoxicity | Moderate - tremor, paresthesia | Elevated - especially viral | Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia | £150‑£200 |

| Tacrolimus | Moderate - less than cyclosporine | Higher - neuro‑psychiatric (headache, insomnia) | Similar to cyclosporine | Diabetes, hyperglycaemia | £180‑£230 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Low | Low | Higher - gastrointestinal infections | GI upset, leucopenia | £120‑£160 |

| Sirolimus | Low | Low | Moderate - wound healing problems | Hyperlipidaemia, oedema | £200‑£250 |

| Azathioprine | Low | Low | Moderate - opportunistic infections | Bone‑marrow suppression | £50‑£80 |

When to choose Neoral over the alternatives

Even with newer drugs on the shelf, many clinicians still start patients on Neoral for specific reasons:

- Established track record: Over 40 years of outcomes data, especially for liver transplants.

- Cost considerations: In some NHS trusts, bulk purchasing keeps the price below newer agents.

- Specific organ protocols: Certain kidney‑transplant centres favor cyclosporine because its nephrotoxicity can be offset by careful dosing.

If a patient has a history of uncontrolled diabetes, Tacrolimus might be a safer bet because it’s less likely to worsen glucose control. Conversely, if the patient is prone to infections, Mycophenolate’s lower renal burden but higher GI infection risk could be acceptable.

Practical checklist for clinicians

- Assess baseline renal function - if eGFR < 30 mL/min, avoid Neoral or Tacrolimus.

- Screen for pre‑existing hypertension - cyclosporine can exacerbate it.

- Check for diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance - favor Mycophenolate or Azathioprine.

- Consider patient adherence - twice‑daily dosing of Neoral may be harder than once‑daily Tacrolimus.

- Plan therapeutic drug monitoring - target trough levels differ: 100‑200 ng/mL (Neoral), 5‑15 ng/mL (Tacrolimus).

Monitoring and safety: What to watch for

Regardless of the drug chosen, regular labs are non‑negotiable. Here’s a month‑by‑month snapshot for the first three months post‑transplant:

| Week | Neoral | Mycophenolate | Tacrolimus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0‑2 | Blood level, creatinine, BP, lipids | CBC, liver enzymes | Blood level, glucose, creatinine |

| 2‑4 | Adjust dose based on trough | Monitor GI tolerance | Check trough, adjust |

| 4‑12 | Monthly labs, eye exam at 6 mo | Monthly CBC, infection screen | Monthly labs, lipid profile |

Eye examinations are crucial for Neoral because chronic use can lead to optic neuritis. For Tacrolimus, fasting glucose checks every month help catch drug‑induced diabetes early.

Future directions: Where immunosuppression is heading

Researchers are combining biologics (e.g., belatacept) with reduced‑dose calcineurin inhibitors to keep rejection rates low while minimizing toxicity. Gene‑editing approaches are still experimental, but the goal is clear: tailor the regimen to each patient’s genetic risk profile.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Neoral still the best first‑line drug for kidney transplants?

Many centres still start with Neoral because long‑term outcome data are robust, but newer protocols increasingly favour Tacrolimus for its slightly lower nephrotoxicity. The choice often hinges on individual renal function and cost.

Can I switch from Neoral to Mycophenolate without a hospital stay?

A switch is possible but should be done under close supervision. Blood levels of Neoral must be tapered while Mycophenolate is titrated, usually over 1‑2 weeks, with weekly labs.

What is the biggest drug‑interaction risk with Neoral?

Cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors (e.g., azole antifungals, certain macrolide antibiotics) can raise cyclosporine levels dramatically, increasing nephrotoxicity risk.

How does the cost of Neoral compare to tacrolimus in the UK?

Neoral typically costs £150‑£200 per month, while Tacrolimus ranges from £180‑£230. Bulk NHS contracts can narrow this gap, but individual prescriptions often show tacrolimus as the pricier option.

Are there dietary restrictions while taking Neoral?

Neoral’s absorption is higher with fatty meals, so consistent timing with food is advised. Grapefruit juice should be avoided because it can boost blood levels.

7 Comments

The pharmaceutical giants have been quietly engineering a monopoly on immunosuppression, and Neoral sits at the very heart of their profit‑driven agenda. While clinicians praise its decades‑long track record, the same data streams are filtered through corporate‑sponsored journals that rarely question the drug’s hidden costs. The cyclosporine formulation was tweaked in the early ’90s just enough to grant new patents, extending exclusivity without delivering genuine therapeutic advantages over older generics. Meanwhile, the subtle shift from Neoral to tacrolimus in many centres is often billed as “clinical progress,” yet the pricing structures reveal a deliberate attempt to steer patients toward higher‑margin products. If you examine the FDA’s advisory committee minutes, you will notice a recurring pattern of undisclosed consultant fees paid to nephrologists who champion these newer agents. The same pattern repeats in the UK, where bulk‑purchase contracts are awarded to firms that promise “future‑proof” drugs, even though long‑term nephrotoxicity data remain sparse. Moreover, the publicly available adverse‑event tables conveniently mask the incidence of hypertension and hyperlipidaemia that surface only after years of chronic exposure. The mechanisms of neuro‑toxicity, often dismissed as “tremor,” are actually early indicators of irreversible central nervous system damage that most post‑transplant care protocols ignore. By contrast, mycophenolate’s side‑effect profile-primarily gastrointestinal-does not carry the same clandestine metabolic sabotage. The reality is that the regulatory agencies are consistently out‑maneuvered by lobbying efforts that prioritize market share over patient safety. A careful review of the UK Transplant Registry shows that centres still using Neoral report higher rates of graft loss associated with renal insufficiency, a statistic rarely highlighted in promotional material. The drug’s reliance on cytochrome‑P450 3A4 metabolism opens a Pandora’s box of interactions, yet prescribing information downplays the lethal potential of concurrent antifungal therapy. In practice, many transplant teams neglect to educate patients about grapefruit juice, inadvertently amplifying cyclosporine levels to toxic thresholds. The whole system thrives on a veil of complexity, making it almost impossible for the average patient to discern whether they are receiving optimal care or simply feeding the pharmaceutical cash‑cow. As a result, the genuine benefits of Neoral become entangled with a web of profit motives, legal loopholes, and selective data dissemination. Until the medical community demands full transparency and prioritizes unbiased comparative trials, the choice between Neoral and its rivals will remain a manufactured dilemma.

Wow, you really dug up the deep‑state script for cyclosporine, didn't you? I guess the next step is to print those secret minutes on a T‑shirt. In reality, most clinicians just want a drug that works without having to decode a conspiracy novel. The side‑effects? Yeah, they're there, but the trade‑offs are part of everyday medicine. So, unless you’re planning to start a whistle‑blower blog, stick to the guidelines.

Papers from the last decade consistently rank cyclosporine’s nephrotoxicity higher than tacrolimus’s, especially in patients with baseline renal impairment. For most kidney transplant protocols, opting for tacrolimus reduces the odds of chronic kidney disease progression.

Your observation touches upon the broader ethical calculus of risk versus benefit, a dilemma that has haunted transplant philosophy since the advent of calcineurin inhibitors. While the statistical data favor tacrolimus in terms of renal preservation, one must also weigh the psychosocial burden of increased neuro‑psychiatric symptoms. The art of medicine lies in harmonising these competing vectors into a patient‑centred trajectory. In that sense, each prescription becomes a miniature moral experiment, guided by both evidence and empathy.

Do you ever wonder why the drug labels are so vague??! The fine print hides a cascade of hidden clauses, each one a potential trigger for an adverse event that the manufacturers never wanted us to see!!! Cyclosporine's interaction with common antibiotics is not a coincidence, it's a deliberate design to keep patients hooked on costly monitoring!!! The surveillance systems are calibrated to report only the mild side‑effects, while the severe cases get buried under layers of bureaucratic jargon!!! And don't get me started on the way insurance companies dictate dosage adjustments - it's like they have a secret playbook for maximizing profit!!!

Hey team, let’s keep the conversation positive and focus on what we can actually do for our patients!!! First off, regular therapeutic drug monitoring is absolutely essential, it catches those sneaky level spikes before they cause real damage!!! Second, educating patients about food interactions, especially grapefruit, can save a lot of headaches down the road!!! Third, don’t forget to schedule those eye exams early, because catching optic neuritis early makes a huge difference!!! And remember, a supportive transplant team that communicates openly reduces stress, which in turn lowers blood pressure-a win‑win for anyone on Neoral!!! So keep pushing those best practices, and the outcomes will speak for themselves!!!

Just remember to check the blood levels every month, it really helps keep things steady.

Write a comment