Pharmacokinetics Dosing Calculator

This tool estimates how your body might process medications based on key pharmacokinetic factors. It's not a substitute for medical advice but helps explain why dosing varies between people.

Ever taken a pill and wondered why it worked for your friend but gave you a headache? Or why your grandma needs a lower dose of the same medicine you take? It’s not luck. It’s pharmacokinetics-the science of how your body moves, changes, and gets rid of drugs. This isn’t just lab jargon. It’s the reason some people get sick from medications while others don’t. And if you’ve ever had an unexpected side effect, chances are pharmacokinetics had a hand in it.

What Happens When You Swallow a Pill?

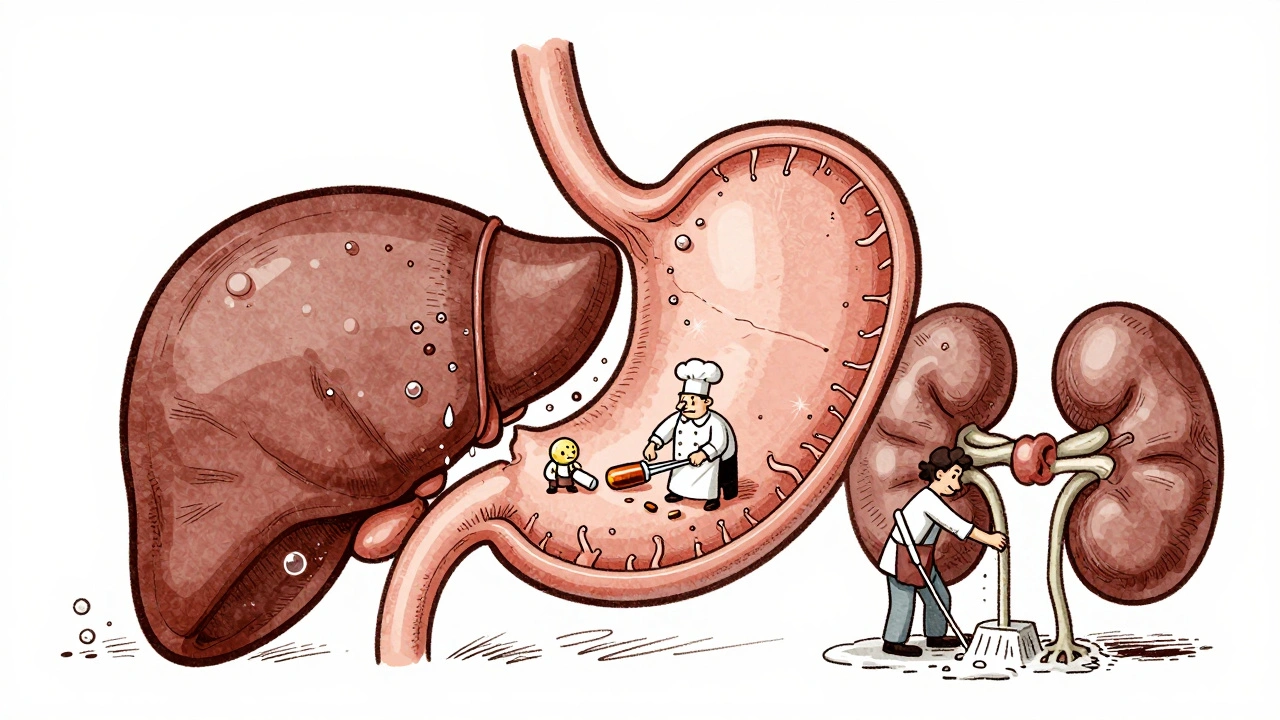

Your body doesn’t just absorb drugs like a sponge. It treats them like intruders that need to be processed, moved, and eventually kicked out. This happens in four stages, known as ADME: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion. Each step is controlled by your biology-and each one can go wrong, leading to side effects.Absorption is how the drug gets into your bloodstream. If you take a pill, it has to survive your stomach acid, pass through your gut lining, and avoid being broken down before it even starts working. Only 40-60% of most oral drugs make it into your blood because of something called "first-pass metabolism." That’s when your liver starts breaking down the drug right after it’s absorbed. IV drugs skip this step and go straight in-100% bioavailability. That’s why some meds are given by injection instead of pills.

Not all drugs absorb the same way. Weak acids like aspirin do better in acidic stomachs (pH 1.5-3.5). Weak bases like codeine need a more alkaline environment. If you’re on antacids or have acid reflux, your body might not absorb your meds properly. And then there’s P-glycoprotein-a protein in your gut that acts like a bouncer, pushing certain drugs back out. Drugs like digoxin can lose 30-70% of their dose to this filter.

Where Does the Drug Go After It Enters Your Blood?

Once in your bloodstream, the drug starts distributing-spreading to tissues and organs. But it doesn’t go everywhere evenly. Some drugs stick to proteins in your blood, like albumin. Warfarin, for example, is 98% bound. That means only 2% is free to work. If another drug kicks warfarin off those proteins, suddenly you’ve got too much active drug in your system. That’s how a simple interaction can turn into a bleeding emergency.The volume of distribution (Vd) tells you where the drug likes to hang out. A low Vd (0.1-0.3 L/kg) means the drug stays mostly in your blood. A high Vd (>1.0 L/kg) means it’s soaking into fat, muscle, or organs like the brain. That’s why some sedatives make you drowsy for days-they’re stored in fat and slowly leak back into your blood.

How Your Liver Changes Your Drugs

The real magic-and danger-happens in your liver. That’s where metabolism kicks in. Your liver uses enzymes, mostly from the Cytochrome P450 family, to turn fat-soluble drugs into water-soluble ones so your kidneys can flush them out. CYP3A4 alone handles half of all prescription drugs.But here’s the catch: your genes decide how fast or slow these enzymes work. About 3-10% of white people are "poor metabolizers" of CYP2D6. That means codeine-designed to turn into morphine in your body-stays as codeine. No pain relief. Meanwhile, "ultrarapid metabolizers" turn it into morphine too fast. That’s how someone can overdose on a normal dose.

Other drugs can mess with this system. Clarithromycin, a common antibiotic, blocks CYP3A4. If you take it with simvastatin (a cholesterol drug), your body can’t break down the statin. Levels spike. Muscle damage, even rhabdomyolysis, can follow. That’s why doctors check your meds before prescribing.

How Your Body Gets Rid of Drugs

Most drugs leave through your kidneys. Your glomerular filtration rate (GFR) determines how fast they’re cleared. Normal GFR? 90-120 mL/min. If you’re over 65 or have kidney disease, that number drops. A 78-year-old with a GFR of 25 mL/min might still get the same vancomycin dose as a healthy 30-year-old. That’s how kidney damage happens. Vancomycin levels build up. Toxicity follows.Some drugs are excreted in bile and end up in poop. Others get filtered by the lungs. But kidneys handle about 80% of drugs. That’s why kidney function tests are routine before starting certain meds. If your doctor doesn’t check your creatinine clearance, they’re guessing your dose.

Why Side Effects Aren’t Random

Side effects aren’t accidents. They’re predictable outcomes of pharmacokinetics. When drug levels go above the therapeutic window, problems start. Phenytoin, an epilepsy drug, is safe at 10-20 mcg/mL. At 20+, 30% of patients develop tremors, confusion, or even coma. At 10-20, only 2% have issues.Some side effects come from metabolites, not the original drug. Diazepam (Valium) breaks down into desmethyldiazepam, which lasts up to 100 hours. In older adults, who clear drugs slower, this builds up. That’s why seniors on long-term benzos fall more often. It’s not the diazepam-it’s the leftover metabolite.

Genetics play a huge role. People with CYP2C9 variants on warfarin have a 5-fold higher risk of bleeding. That’s why genetic testing is now standard for some drugs. Abacavir? HLA-B*5701 screening cuts hypersensitivity reactions by 90%. Clopidogrel? CYP2C19 testing prevents stent clots. These aren’t futuristic ideas. They’re clinical practice today.

Age, Polypharmacy, and Hidden Risks

Older adults are the most vulnerable. By age 70, liver metabolism drops 30-50%. Kidney clearance drops 30-40%. Yet, they take more drugs. On average, Americans over 65 take 4-5 prescriptions daily. That’s 20-30% more chance of a dangerous drug interaction.And it’s not just quantity. It’s timing. Trough levels for drugs like vancomycin must be drawn 30 minutes before the next dose. But studies show 22% of hospital labs get this wrong. If you draw too early, you think the level is low. You give more. You overdose.

Electronic health records miss weight or age 15-20% of the time. That throws off Cockcroft-Gault calculations. A 5-pound error in weight can mean a 20% dosing mistake. That’s enough to turn a safe dose into a toxic one.

What’s Changing Now?

The field is shifting from "one-size-fits-all" to precision dosing. AI tools like DoseMeRx use patient data-age, weight, kidney function, genetics-to predict the perfect dose. They cut vancomycin dosing errors by 62%. The FDA approved this tech in 2021. EMA’s PK4All initiative is building global databases for rare diseases. And the NIH just spent $185 million to fix a glaring gap: 85% of pharmacokinetic studies use Caucasian men under 45. But most patients aren’t.The future? Personalized dosing based on your genes, your liver, your kidneys, your gut bacteria-even your microbiome. Research shows gut microbes metabolize 15-20% of oral drugs. That’s a whole new layer of variability we’re only starting to understand.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a pharmacist to protect yourself. Here’s how:- Know your meds. Ask your doctor or pharmacist: "Is this dose right for me?" Especially if you’re over 65, have kidney or liver disease, or take 3+ drugs.

- Bring a list of everything you take-including supplements and OTCs. Many interactions happen with aspirin, ibuprofen, or St. John’s wort.

- Ask if your drug has a therapeutic range. If yes, ask if monitoring is needed.

- If you feel weird after starting a new drug-dizziness, nausea, rash, muscle pain-don’t ignore it. It might not be "just side effects." It might be a pharmacokinetic mismatch.

- Ask about genetic testing if you’ve had bad reactions before. It’s not sci-fi. It’s covered by insurance for several drugs.

Medicines save lives. But they can hurt too-if we don’t understand how your body handles them. Pharmacokinetics isn’t abstract science. It’s the reason your pills work-or don’t. And knowing how it works might just keep you out of the ER.

What does pharmacokinetics mean in simple terms?

Pharmacokinetics means "what your body does to a drug." It’s the journey a drug takes: how it gets in (absorption), where it goes (distribution), how it’s changed (metabolism), and how it leaves (excretion). It’s not about what the drug does to your body-that’s pharmacodynamics. This is about how your body handles the drug.

Why do some people have worse side effects than others?

Because everyone’s body processes drugs differently. Your genes control how fast your liver breaks down meds. Your kidney function affects how quickly they’re cleared. Your age, weight, other drugs, and even your gut bacteria change how much active drug stays in your system. Two people taking the same pill at the same dose can have completely different outcomes.

Can I test my own pharmacokinetics?

Not directly at home, but your doctor can order tests. Therapeutic drug monitoring checks blood levels of certain meds like warfarin, phenytoin, or vancomycin. Genetic tests can reveal if you’re a slow or fast metabolizer for drugs like clopidogrel or codeine. These aren’t routine for everyone-but they’re used when risks are high or reactions are unexplained.

Do supplements affect how drugs work?

Yes, often. St. John’s wort speeds up CYP3A4, making birth control, antidepressants, and blood thinners less effective. Grapefruit juice blocks CYP3A4, causing statins and blood pressure drugs to build up to dangerous levels. Even calcium supplements can bind to antibiotics like tetracycline and stop absorption. Always tell your pharmacist what supplements you take.

Is it true that older adults are more at risk?

Absolutely. By age 70, liver metabolism drops 30-50%, and kidney clearance drops 30-40%. That means drugs stay in the body longer. Older adults also take more medications, increasing interaction risk. One in three older patients on multiple drugs has an adverse reaction. That’s why dose reductions and careful monitoring are critical.

What’s the biggest mistake people make with meds?

Assuming the dose on the label is right for them. Pills are dosed for an average adult. But if you’re small, old, have kidney issues, or take other drugs, that dose might be too high-or too low. Never adjust your dose without talking to your doctor or pharmacist. A "normal" dose can be toxic for you.

15 Comments

Wow, this is such a needed post! I used to think meds were just 'take one pill' until my grandma had a bad reaction and we found out her kidney function was down. Now I check everything with my pharmacist. So simple, so important.

YES!! 😊 I’m a nurse and I see this ALL the time. People take OTC painkillers with blood thinners and wonder why they’re bruising. It’s not magic-it’s pharmacokinetics. Always ask about interactions! 💊

This is a masterclass in clinical pharmacology. The ADME framework is elegantly explained. One must appreciate how pharmacokinetic variability underpins individualized therapy, especially in geriatric populations with polypharmacy.

Ugh… I just read this and now I’m terrified of every pill I’ve ever taken. Like… what if my liver is secretly a traitor? What if my gut bacteria are plotting against me? I’m not even sure I want to know what’s in my microbiome… 😭

Most people think drugs are like coffee-same cup, same effect. But your body isn’t a vending machine. It’s a complex, genetically coded chemical factory. And if you ignore the manual, you’re asking for trouble. This post nails it.

People who don't get why their meds don't work are just lazy. If you're old or overweight or on 5 pills, you're not the average patient. Stop blaming the drug and start checking your labs. Duh.

So… the FDA approves AI dosing tools… but they still use mostly white male data? That’s not precision medicine. That’s white-washed science. They’re not trying to fix the system-they’re just putting a fancy app on broken foundations.

They don’t want you to know this. Big Pharma profits off one-size-fits-all. If everyone got genetic testing, they’d lose billions. That’s why your doctor doesn’t mention it. It’s not negligence-it’s corporate sabotage.

My pharmacist told me grapefruit juice messes with my statin. So I switched to orange juice. Now I feel great! 🍊✨

That’s great, but did you know orange juice can also inhibit OATP transporters? It’s not just grapefruit. And if you’re on a beta-blocker or fexofenadine, even orange juice can alter absorption. Always check the fine print.

OMG I just realized I’ve been taking my antibiotics with yogurt for years… is that bad?? 😅

Actually, calcium in yogurt can chelate tetracyclines, reducing absorption significantly. But for most other antibiotics, it's fine. Still, best to separate by two hours. Always read the leaflet.

I’ve spent the last decade working with elderly patients on multiple meds, and this post is one of the clearest summaries I’ve ever seen. What’s missing is the human side-how often patients don’t understand why their dose changed, or feel ashamed to ask. We need more education, not just more testing. A 78-year-old woman shouldn’t have to be a pharmacologist just to stay safe. The system should adapt to her, not the other way around.

Microbiome metabolizing 15-20% of oral drugs? That’s wild. I’ve been reading about fecal transplants for C. diff, but now I’m wondering if gut flora could be engineered to optimize drug metabolism. Imagine personalized probiotics as co-therapeutics. This is the future.

Why are we even letting foreigners design our medicine? India’s not even on the map for real science. We need American-led research, American data, American dosing. This ‘global database’ nonsense is just globalism pushing weak science.

Write a comment