The ANDA process is how generic drug makers get legal permission to sell copies of brand-name medicines in the U.S. It’s not a shortcut-it’s a tightly controlled legal pathway built to ensure generics are just as safe and effective as the originals, but at a fraction of the cost. Since the Hatch-Waxman Act passed in 1984, this system has kept 90% of U.S. prescriptions filled with generics, saving consumers over $2.2 trillion in the last decade. But getting that approval isn’t just about filling out forms. It’s a legal and scientific gauntlet that demands precision, documentation, and compliance with federal rules.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

Before 1984, generic drug makers had to repeat every single clinical trial the brand-name company did. That meant spending hundreds of millions and waiting over a decade just to get started. The Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, letting generic companies skip the expensive clinical trials if they could prove their drug was bioequivalent to the original. The law wasn’t just about lowering prices-it was a balance. It gave brand companies 5 years of data exclusivity and patent extensions, while giving generics a clear path to enter the market after patents expired or were challenged.This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, the FDA had approved over 16,892 ANDAs since 1984. That’s not just numbers-it’s millions of people getting affordable insulin, blood pressure meds, and antibiotics because this system works.

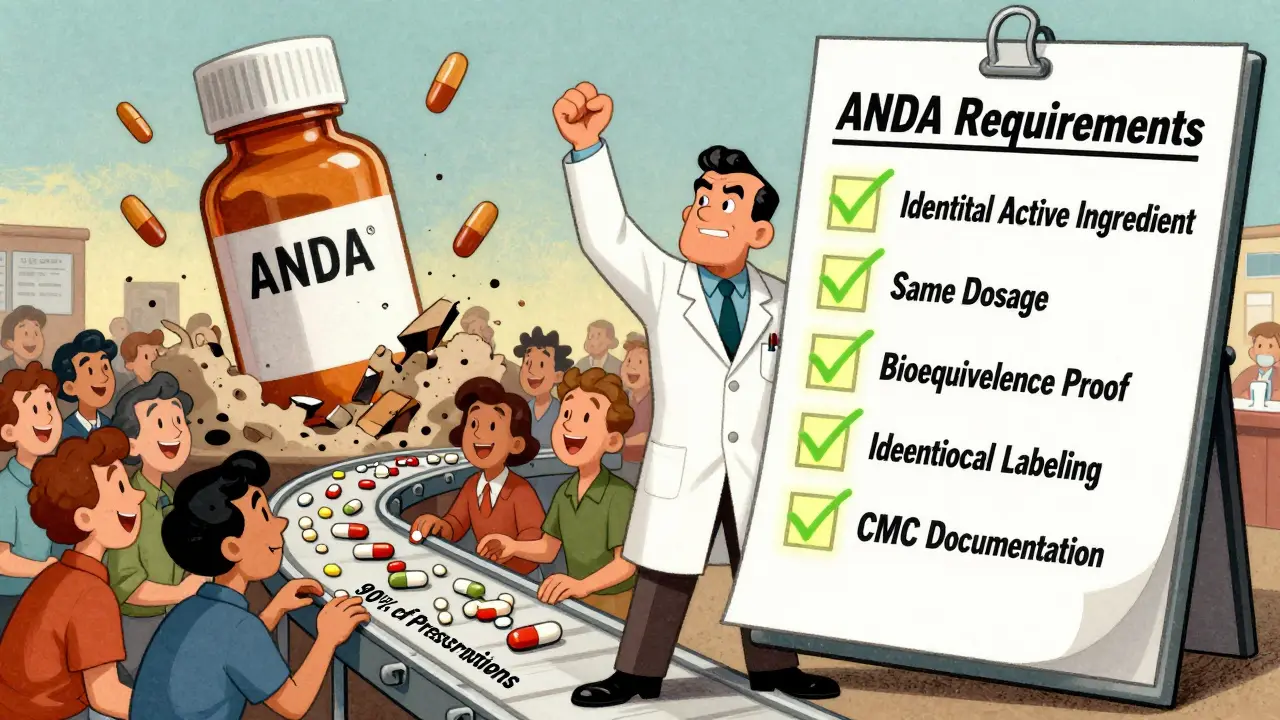

The Core Legal Requirements for an ANDA

The FDA doesn’t accept just any generic submission. There are five non-negotiable legal requirements:- Identical active ingredient: The generic must contain the exact same active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) as the brand-name drug. No substitutions, no alternatives. If you change the salt form or polymorph, you need a special petition under Section 505(j)(2)(C).

- Same dosage form, strength, route, and use: If the brand is a 10mg tablet taken orally once daily, your generic must be the same. No switching to capsules, no changing the dose, no adding new indications.

- Bioequivalence proof: You must show your drug is absorbed into the bloodstream at the same rate and extent as the brand. The FDA requires pharmacokinetic studies where the 90% confidence interval for Cmax and AUC falls between 80% and 125% of the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). This isn’t a suggestion-it’s a hard legal standard written in FDA guidance from 2023.

- Identical labeling: Your package insert must match the brand’s in content, except for minor differences like the generic company’s name or patent expiration dates. You can’t add new warnings or remove existing ones.

- CMC documentation: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) data is the backbone of an ANDA. You must prove your manufacturing process is consistent, your facility follows cGMP rules, your stability data shows the drug won’t degrade before expiration, and your packaging protects the product. This section alone accounts for 23% of all ANDA refusals.

Failure on any one of these points means your application won’t even be reviewed. The FDA has a 147-point checklist for what can trigger a ‘refuse to receive’ decision. Common mistakes? Incomplete bioequivalence protocols (28% of refusals) and weak CMC data.

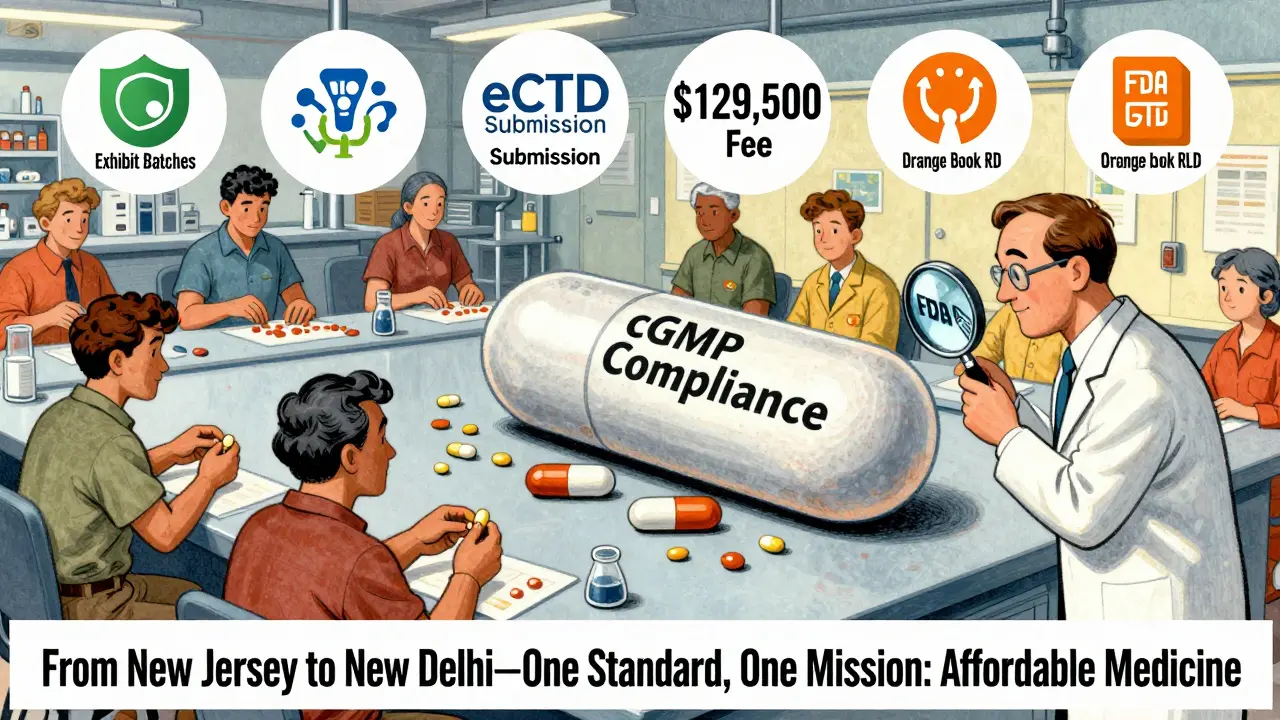

Submission Rules and Fees

You can’t just email your ANDA. It must be submitted electronically in eCTD format-the industry standard for regulatory documents. You also need two forms: FDA-356h (the application form) and FDA-3674 (the user fee cover sheet). And you have to pay. In fiscal year 2024, the fee for a new ANDA is $129,500. For a supplement-say, changing your packaging or adding a new manufacturing site-it’s $5,000.These fees aren’t just bureaucracy. They’re part of the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), which fund the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs. GDUFA III (2023-2027) sets clear performance goals: 90% of standard ANDAs approved within 10 months, priority ones in 8. That’s a big improvement from the 30-month average in 2015.

Manufacturing and Facility Requirements

The FDA inspects every facility that makes the generic drug-whether it’s in New Jersey or New Delhi. You must follow Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), which cover everything from raw material testing to employee hygiene. In 2022, 68% of FDA Form 483 observations (warning letters for violations) were at overseas facilities. That’s not because foreign plants are worse-it’s because more generics are made overseas.You also need exhibit batches-real commercial-scale production runs. The minimum is either 10% of your planned commercial batch size or 100,000 dosage units, whichever is larger. These batches are used for stability testing and must be made under the same conditions as your final product. If you try to cut corners here, your application gets rejected.

Patent Certification and Legal Hurdles

One of the most complex parts of the ANDA is patent certification. You must declare under penalty of perjury which of four statements applies:- Paragraph I: No patent listed for the drug.

- Paragraph II: The patent has expired.

- Paragraph III: The patent expires on a specific date-your product will launch on that day.

- Paragraph IV: The patent is invalid or won’t be infringed.

Paragraph IV is the most controversial. Filing it triggers a 30-month automatic stay on approval, during which the brand company can sue you for patent infringement. This is where many generic launches get stuck. In 2023, a Reddit user with 15 years in regulatory affairs described a case where a Paragraph IV certification led to a 41-month delay, even though the drug was bioequivalent. That’s not a glitch-it’s part of the legal design.

Why Some ANDAs Fail and How to Avoid It

The FDA approved 78.3% of original ANDAs in 2022. That sounds good-but it means nearly a quarter were rejected on first review. Why?- Underestimating CMC: One company had three ANDAs rejected because they didn’t properly validate their container closure system. That’s a $10 million mistake.

- Complex products: Inhalers, topical creams, injectables, and ophthalmic suspensions are harder to replicate. Only 42% of complex generic ANDAs pass on first review, compared to 78% for simple tablets.

- Inconsistent FDA feedback: A 2023 survey found 42% of generic manufacturers struggled with unclear or conflicting comments from reviewers.

Successful companies don’t guess. They use pre-ANDA meetings-1,842 were held in FY2022. These are formal sessions where you present your plan to FDA scientists and get direct feedback. They cost time, but they save millions. Companies like Lupin Limited got approval in under 10 months by submitting a clean, well-prepared application. Others, like Teva, spent $28 million and 42 months on one ANDA for a complex inhaler.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

The ANDA process isn’t just about paperwork. It’s about access. In 2022, generics made up 90.5% of all prescriptions in the U.S. but only 18.1% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition. A brand-name drug might cost $500 a month. The generic? $15. That’s not a coincidence-it’s the result of a legal framework that works.But the system is under pressure. Brand companies are filing more patents on existing drugs-1,450 between 2015 and 2020, according to a JAMA study. These ‘evergreening’ tactics delay generics. The FDA’s 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan is trying to fix that, with new tools to analyze complex products and prevent anti-competitive behavior.

What’s next? AI-assisted document review, faster feedback loops, and more support for complex generics. The goal is clear: keep generics affordable, safe, and available-without sacrificing quality.

What is the difference between an ANDA and an NDA?

An NDA (New Drug Application) is for brand-name drugs and requires full clinical trial data to prove safety and effectiveness. An ANDA is for generics and skips those trials by relying on the FDA’s prior approval of the brand-name drug. The NDA takes 10-15 years and costs over $2 billion. The ANDA takes 3-5 years and costs $5-10 million.

Can a generic drug have different inactive ingredients?

Yes. The active ingredient must be identical, but inactive ingredients (like fillers, dyes, or preservatives) can differ. However, those differences can’t affect how the drug works. If they do, the FDA may require additional testing or reject the application.

How long does it take to get an ANDA approved?

Under GDUFA III, the FDA aims to approve standard ANDAs within 10 months. But in practice, the average is still around 30-36 months, especially for complex products. Delays often come from deficiency letters, patent litigation, or incomplete submissions.

What is a Reference Listed Drug (RLD)?

The RLD is the brand-name drug that the generic is copying. It’s the official standard for bioequivalence testing. The FDA publishes a list of approved RLDs in the Orange Book. You must choose the correct RLD-using the wrong one is a common reason for application refusal.

Do I need a license to submit an ANDA?

You don’t need a specific license to submit an ANDA, but you must have a registered manufacturing facility that complies with cGMP. The FDA inspects that facility before approval. If it fails inspection, your ANDA won’t be approved, even if the application is perfect.

Can a generic drug be approved before the brand-name patent expires?

Yes, but only if you file a Paragraph IV certification claiming the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. That triggers a 30-month legal stay. The FDA can approve the ANDA during that time, but it can’t make the drug available until the stay ends or the patent is invalidated in court.

What Comes Next?

If you’re a generic manufacturer, start by checking the FDA’s Orange Book to find the right Reference Listed Drug. Then run a patent analysis-don’t skip this. Hire a regulatory consultant if you’re new to this. Invest in CMC documentation early. And never underestimate the power of a pre-ANDA meeting. The system rewards preparation, not speed.If you’re a patient, know that the generic you’re taking went through the same legal and scientific rigor as the brand. The FDA didn’t lower the bar-it just removed the redundant steps. That’s how you get affordable medicine without sacrificing safety.

13 Comments

The ANDA framework is a masterclass in regulatory efficiency-bioequivalence thresholds (80-125% CI for Cmax/AUC) aren't suggestions, they're pharmacokinetic bedrock. CMC failures account for 23% of Refuse-to-Receive decisions because manufacturers treat stability protocols like afterthoughts. And don't even get me started on the 147-point FDA checklist-missing one comma on a container closure validation? Application dead. This isn't bureaucracy; it's pharmacological precision engineering.

It’s funny how we call this ‘abbreviated’ when it’s still a 5-year, $10M odyssey 🤔. The real irony? We’re asking for molecular twins while allowing fillers to vary-like demanding identical engines but letting the upholstery be whatever. The system works, sure, but it’s a Rube Goldberg machine built on patent chess and regulatory dogma. 🤷♂️💊

Let me tell you something-this whole ANDA process is the unsung hero of American healthcare. Every time someone picks up a $15 insulin vial instead of a $500 brand-name one, that’s this system working exactly as designed. It’s not perfect, sure-CMC documentation is a nightmare, and overseas inspections are brutal-but think about it: 90% of prescriptions filled with generics? That’s millions of people breathing easier, managing diabetes, surviving hypertension-all because someone took the time to get the polymorph right. Don’t sleep on this. This is public health magic in regulatory drag.

Paragraph IV is a legal trapdoor disguised as innovation. Companies file it to game the system not because the patent’s invalid but because they want to gamble on litigation. The 30-month stay? That’s not protection-that’s extortion by litigation. And don’t get me started on the $129K fee. You think a startup can afford that? Nah. This isn’t about access. It’s about who owns the right to be cheap

Let’s be real-this whole ‘bioequivalence’ thing is a placebo for regulators. You can match AUC and Cmax but still have different dissolution profiles that wreck absorption in real patients. I’ve seen generics that pass FDA specs but make people sick. The system isn’t protecting patients-it’s protecting the illusion of safety. And the FDA? They’re too busy hitting their GDUFA timelines to actually care.

Been in this game 12 years. The pre-ANDA meetings? Game changer. I used to think they were a waste of time-until I got one and the reviewer pointed out we’d used the wrong RLD. Saved us 18 months and $4M. Also-overseas facilities aren’t worse, they’re just under-resourced. FDA inspectors are overworked. The system’s broken, but not because of bad intent. Just bad structure.

The FDA's Orange Book is not a registry-it is a geopolitical minefield. Over 68% of Form 483s originate from non-Western facilities. This is not quality disparity. It is systemic epistemic violence against the Global South. The ANDA process is a colonial apparatus disguised as regulatory science.

The numbers look good but the reality is a black box. Companies game the system with Paragraph IV filings just to delay competition. The FDA approves on paper but doesn't monitor post-market outcomes. We're trading transparency for speed. That's not progress. That's negligence dressed up as efficiency.

Just wanted to say thanks for explaining this so clearly. I didn’t realize generics had to match the brand down to the salt form. And the fact that they can’t change the label? That’s wild. I always thought generics were just cheaper copies-but now I see they’re legally identical. That’s actually kind of beautiful. 🙏

OMG this is so cool!! 🤯 I had no idea generics had to jump through THIS many hoops. Like imagine being a pill and having to prove you’re literally the same as your fancy cousin but cheaper?? The bioequivalence thing with the 80-125% range? Mind blown. And the $129K fee?! That’s a car!! But also… this is why my insulin costs $15 and not $500. Thank you, ANDA, you beautiful, bureaucratic beast 💪💊

So we spent 40 years building a system that lets corporations copy pills but not change the label? The real innovation here is how we turned medicine into a legal crossword puzzle. Meanwhile, the brand companies are filing patents on the color of the tablet. Genius.

For anyone thinking about submitting an ANDA: start with the Orange Book. Pick the right RLD. Then hire a CMC expert before you write a single line of the application. I’ve seen too many teams burn $5M because they thought ‘close enough’ was good enough. It’s not. The FDA doesn’t care if your tablet tastes the same. They care if your dissolution curve matches within 10% over 30 minutes. That’s the line.

Look-I get it. The system’s messy. But let’s not forget what this enables. A single mom in rural Ohio gets her blood pressure med for $3 because this process exists. A veteran in Texas gets his antibiotics without choosing between rent and refills. The paperwork? The fees? The inspections? They’re the cost of keeping the lights on for millions. Don’t hate the machine-help fix it. Pre-ANDA meetings aren’t optional. They’re your lifeline. And if you’re reading this? You’re already one step ahead.

Write a comment