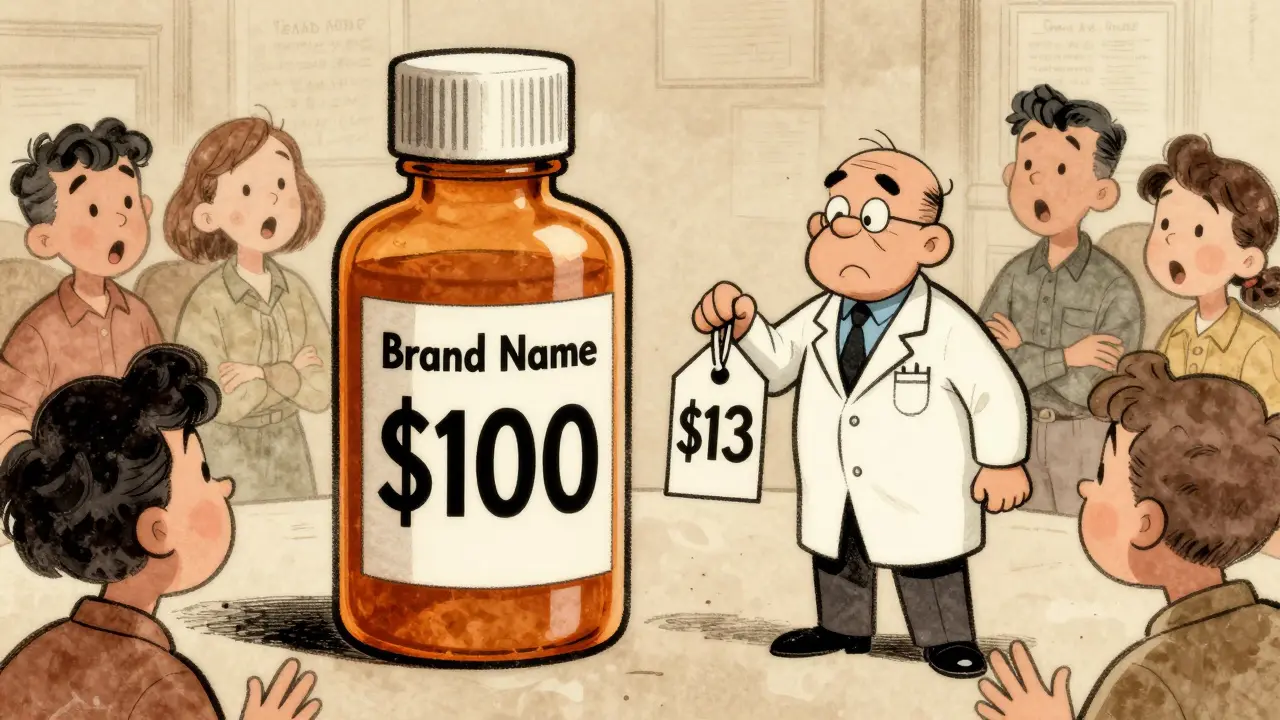

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 13% of the original price. That’s a big drop. But here’s what most people don’t realize: the real savings come after that first generic. When a second company starts making the same drug, prices don’t just dip-they plummet. And when a third company joins, the price often falls to less than half of what it was when the first generic arrived.

Why the second generic changes everything

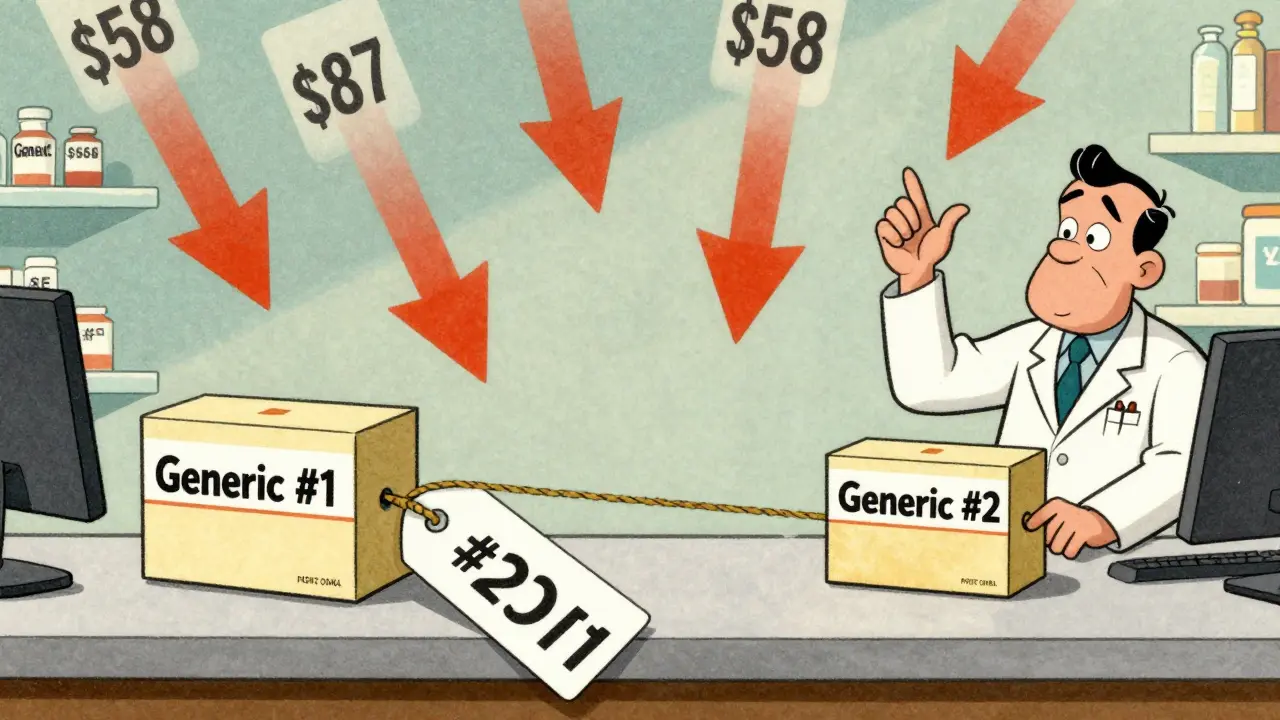

The first generic maker has a window of opportunity. They’re the only alternative to the brand, so they can charge more than they would if there were others competing. But that doesn’t last. Once a second company gets FDA approval and starts producing the same drug, everything shifts. Suddenly, there’s a choice. Pharmacies and wholesalers can play one supplier off the other. The first generic maker can’t raise prices anymore-they’ll lose business. So they lower them. Sometimes by 30%, sometimes more. Data from the FDA shows that after the first generic enters, the average price drops to about 87% of the brand’s original price. But when the second generic enters, that number crashes to 58%. That’s not a small adjustment. It’s a 31-point drop in a matter of months. For a drug that cost $100 a month under the brand, that means the price falls from $87 to $58. That’s $29 saved every month. For someone on a chronic medication, that’s hundreds of dollars a year.The third generic hits like a hammer

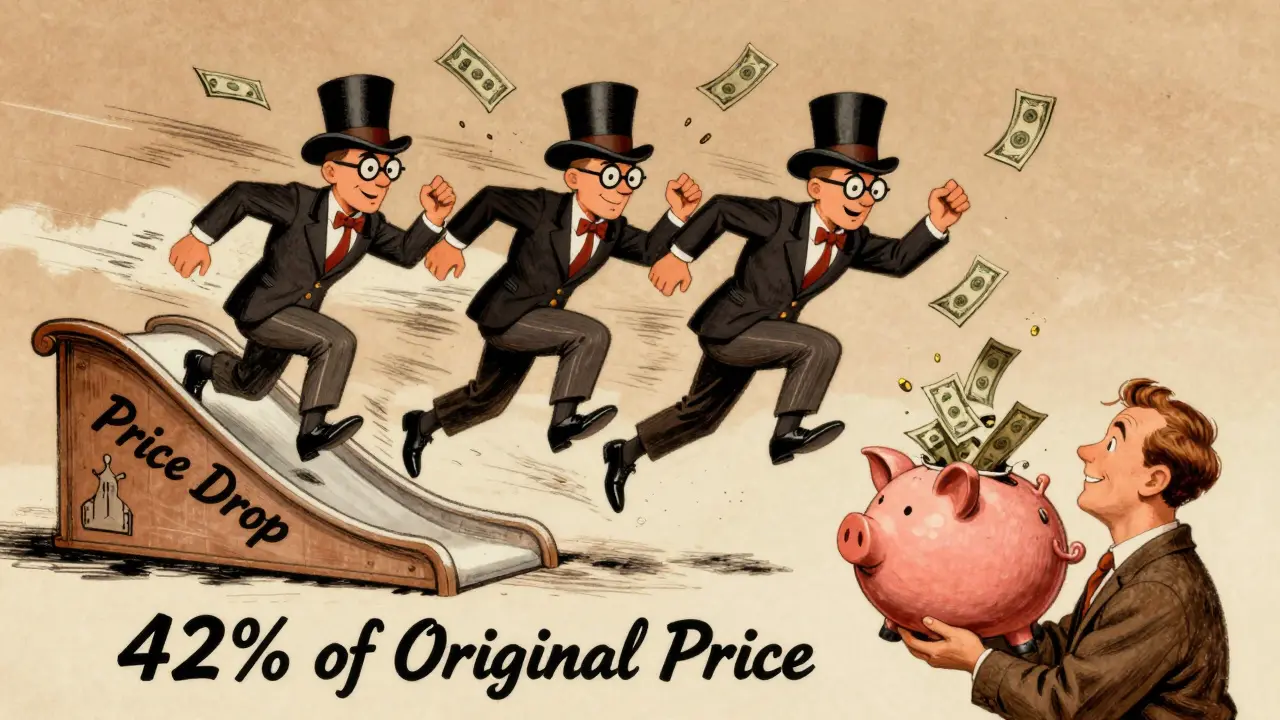

The third generic doesn’t just add to the competition-it multiplies it. By the time a third manufacturer enters, the market is no longer a quiet auction. It’s a bidding war. Each company is trying to win contracts with big pharmacy chains and health plans. The only way to win is to undercut the others. And they do. The FDA found that with three generic makers, prices fall to just 42% of the original brand price. That’s more than a 50% drop from the second generic’s price. In some cases, the price drops even further-down to 30% or lower-when more companies join. For high-cost drugs like those used to treat hepatitis C or certain cancers, this can mean the difference between a patient being able to afford their medicine or skipping doses. This isn’t theoretical. In 2020, a generic version of the cholesterol drug rosuvastatin had three manufacturers. One sold it for $12 a month. Another for $9. The third for $7. The pharmacy benefit managers didn’t just pick the cheapest-they negotiated deeper discounts because they had leverage. Patients paid less. Insurers paid less. Everyone won.What happens when competition stalls

But not all markets work this way. In nearly half of all generic drug markets, only two companies make the drug. That’s called a duopoly. And in a duopoly, prices don’t always fall. Sometimes, they rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida found that when a third manufacturer exits a market-either because they can’t compete or because they’re bought out-the price often jumps by 100% to 300%. That’s not a typo. One drug, when competition dropped from three to two manufacturers, went from $1.50 per pill to $4.50. Patients were shocked. Pharmacists were confused. The reason? With only two players, there’s less pressure to undercut. They can tacitly agree to keep prices stable-or even raise them together. This is why the entry of a third generic isn’t just nice to have-it’s critical. It breaks the fragile balance that lets two companies control the market. Without that third entrant, patients pay more. Insurance plans pay more. And the system becomes less predictable.

Who’s really holding prices down?

You might think pharmacies or insurers are the ones driving prices lower. But they’re not. They’re just the middlemen. The real price pressure comes from manufacturers competing directly with each other. Think of it like this: a pharmacy doesn’t decide how much to charge for a drug. They buy it from a wholesaler, who buys it from the manufacturer. The manufacturer sets the price. And if there are three manufacturers, they all know that if they charge too much, the others will undercut them. So they race to the bottom. The problem? The supply chain is getting more concentrated. Three companies-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-control 85% of the wholesale market. Three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) handle 80% of prescriptions. These giants have enormous power. They can demand deep discounts, but they can also push manufacturers to cut costs so aggressively that production becomes risky. That’s why some generic drugs disappear. If the price falls too low, a manufacturer might shut down production because it’s no longer profitable. That’s how shortages happen. And when a manufacturer exits, the competition drops. And prices creep back up.How big is the savings?

The numbers are staggering. Between 2018 and 2020, the FDA approved 2,400 new generic drugs. Thanks to competition between multiple manufacturers, those drugs saved patients and the health system $265 billion. That’s not a guess. That’s an official estimate from the federal agency responsible for drug safety and approval. The biggest chunk of that savings came from drugs with three or more generic makers. The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at HHS found that markets with three competitors saw price reductions of about 20% within three years. Markets with ten or more competitors saw reductions of 70% to 80%. Compare that to brand-name drugs. While generics are competing on price, brand drugs have no competition. Patents block anyone else from making them. So prices can rise year after year-sometimes by 10%, 20%, even 50% in a single year. That’s why a drug that cost $50 in 2015 might cost $200 in 2025.

What’s blocking more competition?

You’d think more companies would rush in to make cheap generics. But they don’t always. There are two big reasons. First, brand companies use legal tricks to delay generics. One common tactic is called “pay for delay.” The brand company pays a generic maker to stay out of the market. In exchange, the generic company gets a cut of the brand’s profits. The Federal Trade Commission estimates this costs patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs. In total, these deals cost the system nearly $12 billion annually. Second, some brand companies file dozens of patents-not because the drug has new features, but just to keep generics out. One drug had 75 patents filed over time, extending its monopoly from 2016 all the way to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction. The FDA and Congress are trying to fix this. The CREATES Act, passed in 2022, makes it harder for brand companies to block generic access to samples needed for testing. New legislation is also targeting “pay for delay” deals. But progress is slow.What patients can do

You can’t control how many companies make your drug. But you can control whether you pay more than you have to. If you’re on a generic drug, ask your pharmacist: “How many companies make this?” If the answer is one or two, ask if there’s a version made by another company. Sometimes, switching to a different manufacturer can cut your cost in half. Also, don’t assume your insurance’s preferred brand is the cheapest. Many PBMs have contracts with specific generic makers. If your drug has three manufacturers, ask your insurer if they cover the lowest-priced version. And if you’re paying cash, use a price comparison app. Some apps show you the difference between the $12 version and the $5 version of the same pill. It’s not magic. It’s just competition.The future of generic pricing

Analysts predict generic drug prices will keep falling-by 3% to 5% a year through 2027. But that’s only if enough companies keep entering the market. If consolidation continues-if only five big players control 90% of generic production-then the magic of the second and third generic will fade. The lesson is clear: competition is the only thing that keeps drug prices low. Not regulation. Not negotiation. Not goodwill. Just competition. The FDA, Congress, and health experts all agree: the entry of the second and third generic is the most powerful tool we have to lower drug costs. Anything that slows that down-whether it’s legal tricks, corporate mergers, or supply chain bottlenecks-ends up hurting patients. So the next time you see a generic drug price drop, don’t just thank your pharmacist. Thank the second and third companies that made it possible.Why does the price of a generic drug keep dropping after the first one comes out?

Because each new generic manufacturer enters the market to compete for business. They undercut each other’s prices to win contracts with pharmacies and insurers. The first generic has no competition, so it charges more. The second cuts the price significantly. The third cuts it even more. By the time three or more companies are making the same drug, prices often fall to 40% or less of the original brand price.

Is a generic drug with only two manufacturers cheaper than the brand?

Usually, yes-but not as cheap as it could be. A generic with two manufacturers typically costs 50-60% less than the brand. But if a third manufacturer entered, the price could drop another 30-40%. Markets with only two makers often miss out on the biggest savings because there’s less pressure to cut prices.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly get more expensive?

When a manufacturer exits the market-because it’s not profitable anymore-the number of competitors drops. If a drug goes from three makers to two, prices often rise by 100% or more. This happens because the remaining companies no longer need to undercut each other. They can raise prices without losing customers.

Do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) lower generic drug prices?

PBMs don’t create price competition-they just negotiate within it. Their leverage increases when there are more generic manufacturers. With three or more makers, PBMs can demand deeper discounts. But if only one or two companies make the drug, PBMs have little power to lower prices. The real price pressure comes from manufacturers competing against each other.

Can I ask my pharmacist for a cheaper version of my generic drug?

Absolutely. Many generic drugs are made by multiple companies, and they can vary in price by 50% or more. Ask your pharmacist: “Is there another manufacturer that makes this drug? Which one is the least expensive?” Switching to a different generic version can save you hundreds a year.

Are there laws to stop drug companies from blocking generic competition?

Yes. The CREATES Act (2022) makes it illegal for brand companies to block generic makers from getting drug samples needed for testing. Other bills target “pay for delay” deals, where brand companies pay generics to delay entry. These practices are still common, but lawmakers are working to shut them down.

9 Comments

Man, I had no idea the third generic could drop prices that hard. My insulin went from $80 to $22 in six months after another company jumped in. I thought it was a glitch. Turns out it was just capitalism doing its job.

Never thought I'd be grateful for drug companies fighting each other, but here we are.

This is the kind of systemic exploitation that only happens in capitalist dystopias. The fact that life-saving medicine is subject to bidding wars between corporations is obscene. India produces 60% of the world's generics-not because we're cheap, but because we refuse to let patents become death sentences.

Meanwhile, Americans celebrate $7 pills like it's a miracle, when it should be a basic human right.

Big shoutout to the pharmacists who actually know this stuff and will help you switch generics! I used to pay $140 for my blood pressure med until my pharmacist said, 'Hey, there's a $12 version made by a company in Tennessee.' I was skeptical-but I switched and saved $1,500 a year.

Don’t just take the first generic your insurance pushes. Ask. Push back. You have more power than you think. This isn’t magic-it’s just competition, and it works.

Wait… so you're telling me the government didn't just magically lower drug prices? That the corporations themselves are secretly fighting each other to make things cheaper? That sounds like a CIA psyop.

What's the real agenda here? Are PBMs secretly owned by Big Pharma? Did the FDA get bought? I've seen the videos. There are cameras in the pill bottles. They're watching us.

so like third generic = price drops

but why dont they just make more

why is this even a thing

people die over this

why is this hard

its just a pill

why is this so complicated

why do we even have patents

why not just make all drugs free

why is this a debate

its a fucking pill

Let’s be real-the entire system is a rigged game where the illusion of competition is maintained to justify profit extraction. The FDA approves generics, but the real bottleneck is in the supply chain consolidation. McKesson, Cardinal, AmerisourceBergen-they’re not neutral distributors. They’re gatekeepers who dictate which manufacturer gets shelf space.

And PBMs? They’re not saving you money-they’re taking a cut from every transaction and steering you toward the ones that pay them the highest rebates. The 'cheapest' pill isn’t always the cheapest for you-it’s the one with the biggest kickback.

This isn’t about competition. It’s about structural capture. The third generic doesn’t fix the system-it just redistributes the pain a little more evenly until the next consolidation wave wipes it all out.

my mom had to stop her heart meds because the price went up again and now she’s in the hospital and i just want to cry why is this happening why can’t we fix this

In India, we see this every day. A drug that costs $50 in the U.S. costs less than $2 here because 12 companies make it. No one makes a fortune-but everyone gets the medicine.

What’s missing isn’t technology or science. It’s the political will to treat health like a public good, not a stock ticker.

Maybe if more Americans saw how it works elsewhere, they’d stop celebrating $7 pills as miracles.

That’s actually brilliant. I never thought about it like that. I just assumed generics were all the same. Turns out I’ve been overpaying for years. My pharmacist didn’t even mention there were different makers. Maybe I should ask next time.

Write a comment