Pulmonary Embolism Risk Assessment for Athletes

Assess Your Risk

This tool helps you identify your personal risk factors for pulmonary embolism based on your training routine, travel habits, and health factors.

Your Risk Assessment

Risk Score

Risk Level

Key Risk Factors Identified:

Key Takeaways

- Athletes can develop pulmonary embolism (PE) despite high fitness levels.

- Long‑duration travel, intense training, dehydration, and underlying clotting disorders are the biggest triggers.

- Early recognition of chest pain, shortness of breath, or sudden fatigue can save lives.

- Prevention hinges on proper hydration, mobility during travel, and use of compression gear when risk is high.

- Return‑to‑play is a staged process that balances anticoagulation therapy with progressive training.

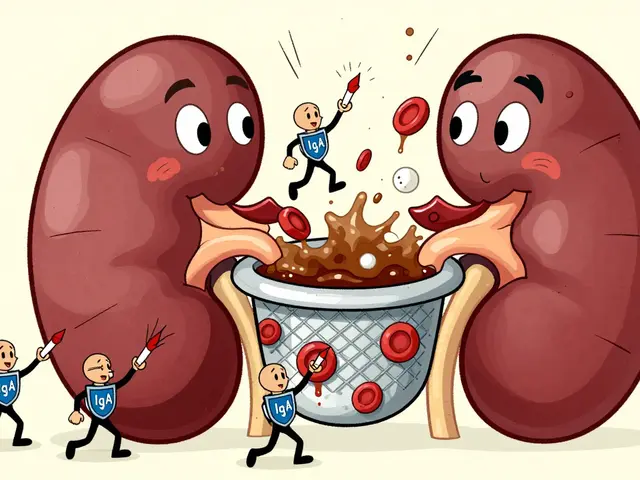

What Is Pulmonary Embolism?

When a clot travels to the lungs and blocks a pulmonary artery, it creates a potentially life‑threatening blockage known as a pulmonary embolism. The condition is part of the broader spectrum called Venous Thromboembolism, which also includes deep‑vein thrombosis (DVT). In healthy athletes, the risk is lower than in sedentary people, but specific sport‑related factors can tip the balance.

Why Athletes Are Not Immune

People assume that a strong heart and regular exercise shield them from blood clots. In reality, several sport‑specific scenarios increase clot formation:

- Prolonged immobility during travel - a 12‑hour flight to a competition creates venous stasis, especially in the legs.

- Intense, repetitive training - micro‑injuries to the endothelium can expose tissue factor and kick‑start the clotting cascade.

- Dehydration - loss of plasma volume concentrates blood, raising viscosity.

- Use of performance‑enhancing substances - anabolic steroids and erythropoietin boost red‑cell mass, thickening blood.

- Underlying clotting disorders - Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, or antiphospholipid syndrome may be undiagnosed until a PE occurs.

Common Triggers in Sports

Here are the most frequently reported scenarios that have led to PE in athletes:

- Marathon runners who neglect fluid intake during a race.

- Cyclists on multi‑day tours who sit on a narrow saddle for hours.

- Soccer teams flying across continents without leg‑movement breaks.

- Weight‑lifters using high‑dose anabolic steroids.

- Contact‑sport athletes who sustain lower‑leg fractures, prompting immobilization.

Spotting the Warning Signs

Early symptoms can be subtle, especially when an athlete attributes them to “just a tough training day.” Keep an eye out for:

- Sudden shortness of breath, especially at rest.

- Sharp, pleuritic chest pain that worsens with deep breaths.

- Unexplained rapid heart rate (tachycardia).

- Feeling light‑headed or faint during or after exercise.

- Swelling or tenderness in one leg - a clue that a DVT may have formed.

How Doctors Diagnose PE

The diagnostic pathway blends clinical judgment with a few key tests:

- D‑dimer test - a blood marker that rises when clot breakdown occurs. A normal result can rule out PE in low‑risk patients.

- CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) - the gold‑standard imaging that visualises clots within the pulmonary arteries. CT Pulmonary Angiography offers rapid, high‑resolution answers.

- Compression ultrasound of the legs - detects DVT, which often co‑exists with PE.

When the suspicion is high, clinicians will proceed directly to imaging, even if the D‑dimer is borderline.

Prevention Strategies Tailored for Athletes

Prevention is a blend of lifestyle tweaks and, when needed, medical interventions. Below is a practical toolbox:

- Hydration protocols - sip electrolyte‑rich fluids every 15‑20 minutes during long sessions or races.

- Compression stockings - graduated compression (15-20mmHg) helps venous return during flights or prolonged sitting. Compression Stockings are lightweight and can be worn under training gear.

- Mobility breaks - stand, march in place, or perform ankle‑circles for 2‑3 minutes every hour on a plane or bus.

- Gradual training ramps - avoid sudden spikes in intensity or volume; follow a 10% rule (increase load no more than 10% per week).

- Screening for clotting disorders - athletes with a family history of VTE should consider a simple thrombophilia panel.

- Medication review - discuss any hormonal therapy, contraceptives, or steroid use with a physician.

Recovery and Return‑to‑Play

Once a PE is confirmed, treatment typically starts with anticoagulation therapy. The goal is to prevent new clots while the existing one dissolves.

- Initial phase (first 5‑7 days) - low‑molecular‑weight heparin (LMWH) given subcutaneously.

- Transition phase (weeks 1‑3) - switch to an oral direct‑acting anticoagulant (e.g., apixaban or rivaroxaban). Doses are weight‑adjusted.

- Maintenance phase (3‑6 months) - continue oral anticoagulant; periodic blood tests monitor kidney function and drug levels.

Return‑to‑play isn’t a simple “off‑the‑clock” decision. Most experts require:

- At least 4 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation with stable INR (if using warfarin) or consistent drug levels.

- Resolution of symptoms and clearance on a repeat CTPA or ventilation‑perfusion scan.

- Gradual re‑introduction of activity - start with low‑impact cardio, then progress to sport‑specific drills under physiotherapy supervision.

- Ongoing risk assessment - if a hereditary clotting disorder is present, lifelong anticoagulation may be recommended, influencing sport eligibility.

Psychological support is also vital; many athletes feel anxiety about re‑injuring themselves. A sports psychologist can help rebuild confidence.

Pre‑Game Checklist for Athletes & Coaches

- Confirm hydration status (urine color light yellow, no signs of cramps).

- Wear compression stockings on travel days longer than 4hours.

- Schedule leg‑movement breaks - set a timer on the flight or bus.

- Review medication list for any clot‑promoting substances.

- Ask medical staff about personal or family history of VTE.

- If recent injury, ensure proper immobilization technique to avoid venous stasis.

Risk‑Factor Comparison: General Population vs Athletes

| Risk Factor | General Population | Athletes |

|---|---|---|

| Immobility | Prolonged bed rest, sedentary job | Long‑haul travel, post‑injury casting |

| Dehydration | Occasional | Frequent during endurance events |

| Hormonal influences | Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement | High‑dose anabolic steroids, testosterone therapy |

| Underlying thrombophilia | Rarely screened | Often screened in elite programs |

| Inflammation | Low‑grade chronic disease | Acute post‑exercise inflammation |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a fit, young athlete really get a pulmonary embolism?

Yes. While the overall incidence is lower, sport‑related factors like long travel, dehydration, and certain substances can create the perfect storm for a clot, even in highly fit individuals.

What immediate steps should I take if I suspect a PE during training?

Stop activity, sit or lie down, and call emergency services. Provide details about chest pain, shortness of breath, and any recent travel or leg swelling. Do not take any medication unless prescribed.

How long does anticoagulation therapy usually last?

For a first‑time, provoked PE (e.g., after a long flight) the typical course is 3‑6 months. Unprovoked or hereditary cases may require lifelong therapy.

Are compression stockings mandatory for every athlete?

They are strongly recommended for any situation involving prolonged immobility-flights longer than 4hours, long bus trips, or after lower‑leg injury requiring limited movement.

Can I continue using NSAIDs after a PE diagnosis?

Short‑term NSAIDs are generally safe, but they can increase bleeding risk when combined with anticoagulants. Discuss any pain‑relief plan with your physician.

Next Steps & Troubleshooting

If you or a teammate experiences any of the warning signs, act fast: call emergency services, note recent travel or training patterns, and inform the medical team about any medication or supplement use. For those who have already been diagnosed, keep a log of anticoagulant dosing, hydration intake, and any side‑effects. Should you encounter unexplained bruising or bleeding, contact your doctor immediately - it may signal over‑anticoagulation.

Finally, embed these prevention habits into your regular routine. Over time, they become second nature, letting you focus on performance rather than worry.

12 Comments

Another so‑called “expert” trying to parade a checklist like it’s a miracle cure. The drama of calling every athlete a ticking time‑bomb feels a bit over‑the‑top, honestly.

Excuse the interuption, but the previous post is riddled with grammtical errors – “Its” should be “its”, and “their” should be “there”. As a Brit I can assuer you that proper punctuation is a sign of civilisation. Also, the speling of “travelling” is wrong – we keep the double‑l.

Honestly, this reads like a recycled health pamphlet – dramatized for clicks. If you think athletes are immune, you’re living in a fantasy.

First off, congratulations on tackling a topic that many coaches simply ignore. Pulmonary embolism, while rare in athletes, can be precipitated by the exact factors you outline-dehydration, prolonged immobility, and even certain supplements. The key to prevention starts the night before travel: load up on electrolyte‑rich fluids and avoid alcohol, which can further dehydrate you. During a long flight, set an alarm every hour to stand, walk the aisle, or at least do ankle pumps to keep the venous return moving. If you have a known thrombophilia, consider a low dose of aspirin after consulting your hematologist, as it can blunt platelet activation. Compression stockings are not just for the elderly; graduated 15‑20 mmHg sleeves fit comfortably under most training shoes and make a measurable difference in leg‑vein flow. When you return to training after a confirmed PE, start with low‑impact activities such as stationary cycling or elliptical work for a week before progressing to jogging. Maintain your anticoagulation regimen as prescribed-missing doses can lead to rebound clotting, which is far more dangerous than the medication side‑effects. Watch for subtle signs like a lingering leg ache or a mild increase in resting heart rate; these can be early warnings before full‑blown symptoms appear. If you experience chest pain that worsens with deep breaths, stop immediately and seek emergency care; time is muscle and time is lung tissue. Psychological support is often overlooked, but many athletes develop anxiety about returning to competition after a PE, so consider speaking with a sports psychologist. Document every training session, medication change, and travel itinerary in a health log; patterns emerge that can guide future preventative measures. Educate your teammates and coaching staff-awareness spreads faster than a clot, and early recognition can save lives. Finally, remember that a single episode does not define your career; many athletes come back stronger with the right medical guidance. Stay proactive, stay hydrated, and keep your legs moving-your lungs will thank you.

Listen up, fellow athletes!!! We all know the British are the epitome of discipline-so why not adopt our travel routines?!! Pack those compression stockings, sip water like it’s tea, and keep those legs marching!!! 😊🚀

Enough with the fluff-if you’re not hydrating, you’re just asking for a clot. Cut the nonsense and get moving.

It’s a tragic masterpiece, this battle between the heart and the hidden menace of clotting. We’re talkin’ about blood that’s thicker than a winter’s fog, and the stakes are as high as the podium. Definately, the only way out is through vigilance and a dash of common sense. So lace up those socks, sip that electrolyte‑laden drink, and remember: the body will betray you if you betray it.

Thank you for sharing this comprehensive overview. I would like to add that regular follow‑up ultrasounds can verify DVT resolution before clearing an athlete for full activity. Maintaining clear communication with the team physician ensures a safe return‑to‑play timeline.

Dear author, I commend the thoroughness of this guide and the sensitivity with which you address such a serious condition. The emphasis on early symptom recognition is particularly valuable for athletes who may otherwise dismiss warning signs. I hope this information reaches coaches and medical staff alike, fostering a culture of proactive care. Please accept my sincere appreciation for your dedication to athlete health.

Yo, I gotta jump in here-did anyone actually read the part about compression socks? 😂 They’re not just for grandma, they work for us marathoners too! 👟💨

From a physiological standpoint, the interplay between shear stress and endothelial activation during prolonged low‑flow states is a classic trigger for coagulation cascades. The guide nails the practical mitigation strategies, especially the ankle‑pump protocol, which aligns with current consensus guidelines. Keep the conversation going, folks.

cleerly, only the truly erudite grasp the nuance herein.

Write a comment