Smoking is a behavior that introduces nicotine and a mixture of over 7,000 chemicals into the body, many of which are proven carcinogens. While most people link it to lung disease, the truth is that smoking fuels a wider cancer epidemic. This article untangles the link between smoking and the spectrum of cancers that often stay off the headlines.

Why every cancer matters, not just the lungs

When the World Health Organization (WHO) declares a habit a “major cancer risk,” it’s based on population‑wide studies that measure relative risk (RR). For tobacco, the RR for lung cancer tops 20, but for other sites it ranges from 2 to 7, still enough to shift public‑health priorities.

Key cancers tied to smoking

Below are the most studied cancers where smoking markedly raises risk. Each entry begins with a concise definition marked up for easy schema extraction.

Cancer is a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell growth that can invade surrounding tissues and spread to other parts of the body.

Lung Cancer is a malignant tumor arising from the respiratory epithelium, responsible for roughly 1.8 million deaths worldwide each year.

Head and Neck Cancer is a collective term for malignancies of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx, accounting for about 650,000 new cases globally annually.

Bladder Cancer is a cancer originating in the urothelium of the bladder, with smoking contributing to up to 50% of diagnoses in men.

Pancreatic Cancer is a high‑grade malignancy of the exocrine pancreas, known for a five‑year survival under 10%.

Cervical Cancer is a malignancy of the cervical epithelium, where smoking acts as an independent co‑factor alongside HPV infection.

Secondhand Smoke is a mixture of sidestream and exhaled smoke that non‑smokers inhale, carrying many of the same carcinogens as active smoking.

Risk numbers that tell the story

Researchers at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) have pooled data from more than 150 cohort studies. The table below captures the relative risk for ever‑smokers compared with never‑smokers, together with approximate incidence rates in high‑income countries.

| Cancer Type | Relative Risk (Ever vs Never) | Incidence per 100,000 (smokers) | Key Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 20‑30 | 65 | Highest burden; risk drops 10% per year after quitting |

| Head & Neck | 4‑6 | 12 | Synergy with alcohol amplifies risk |

| Bladder | 3‑4 | 15 | Risk persists 20years after cessation |

| Pancreatic | 2‑3 | 8 | Combined with obesity, RR can exceed 4 |

| Cervical | 2‑2.5 | 5 | Interaction with HPV, risk drops after 10 years quit |

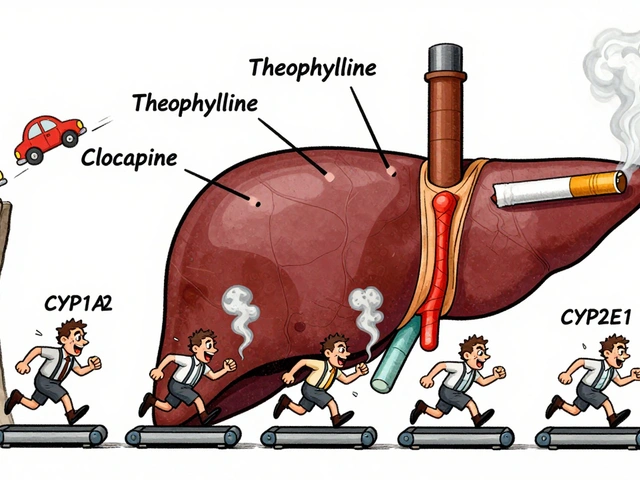

How tobacco chemicals turn healthy cells malignant

Every puff delivers nicotine, tar, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrosamines, and heavy metals such as cadmium. These agents drive carcinogenesis through three main pathways:

- DNA adduct formation: PAHs bind directly to DNA, creating mutations in tumor‑suppressor genes like TP53.

- Chronic inflammation: Irritation of mucosal linings triggers cytokine release, fostering a micro‑environment where abnormal cells thrive.

- Immune suppression: Nicotine alters T‑cell activity, reducing surveillance that would normally eliminate rogue cells.

These mechanisms are not limited to the lungs; the bloodstream distributes the carcinogens to the bladder, pancreas, and even the cervix, explaining the wide‑reaching impact.

Secondhand smoke: the silent contributor

Non‑smokers exposed to secondhand smoke face a 20‑30% higher risk of lung cancer and a 15‑20% increase for head‑and‑neck cancers. Children in smoke‑filled homes see higher rates of nasal cancers and oral leukoplakia. The WHO classifies secondhand smoke as an independent Group1 carcinogen, underscoring that the danger extends beyond the smoker.

Public‑health milestones and remaining gaps

Since the 1964 US Surgeon General report, tobacco control has saved an estimated 8million lives worldwide. Key strategies include:

- Tax hikes that raise the price of cigarettes by at least 10%.

- Graphic pack warnings that cover at least 50% of the surface.

- Smoke‑free policies in workplaces, restaurants, and public transport.

Despite progress, low‑income countries now hold 80% of the global smoking population, and the rise of heated tobacco products threatens to stall declines. A 2023 IARC monograph warned that emerging products still emit carcinogenic particles, though at lower concentrations.

What individuals can do right now

For anyone concerned about the broader cancer risk, the following steps are practical and evidence‑based:

- Quit now: Within one year, the excess risk for head‑and‑neck cancers drops by 30%.

- Seek professional help: Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) combined with behavioral counseling improves quit rates to 30‑35%.

- Screen regularly: Low‑dose CT scans for lung cancer, oral examinations for head‑and‑neck lesions, and urine cytology for bladder cancer are recommended for long‑term smokers over age 50.

- Protect others: Enforce smoke‑free homes and cars, especially around children and pregnant partners.

These actions not only lower cancer risk but also improve cardiovascular health, respiratory function, and overall quality of life.

Related concepts and next steps in your health journey

Understanding the smoking‑cancer link opens doors to deeper topics such as:

- Epidemiology of tobacco‑related disease: How researchers track patterns across populations.

- Genetic susceptibility: Why some smokers develop cancer while others do not.

- Policy advocacy: Ways to influence local smoking bans and taxation.

Exploring these areas will reinforce the reasons behind quitting and help you become an informed advocate for your own health and community.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does smoking increase the risk of cancers other than lung cancer?

Yes. Smoking raises the risk of head‑and‑neck, bladder, pancreatic, cervical, esophageal and several other cancers. Relative risks typically range from 2 to 6 for regular smokers compared with never‑smokers.

How long does it take for cancer risk to lower after quitting?

Risk declines gradually. For lung cancer, excess risk halves after about 10years. For head‑and‑neck cancers, a 30% reduction is seen within the first year, and bladder cancer risk can remain elevated for up to 20years before normalising.

Is secondhand smoke really dangerous for cancer?

Absolutely. Non‑smokers exposed to household or workplace smoke have a 20‑30% higher chance of developing lung cancer and a noticeable increase in head‑and‑neck and bladder cancers. Children are especially vulnerable.

Can e‑cigarettes or heated tobacco products reduce cancer risk?

Evidence is still emerging. While they emit fewer tar particles, they still release nicotine, formaldehyde and other carcinogens. The IARC classifies them as possibly carcinogenic, so they are not a proven safe alternative.

What screening tests are recommended for long‑term smokers?

Low‑dose CT for lung cancer (annually for ages 55‑80 with 30+ pack‑years), oral examinations by a dentist or ENT specialist for head‑and‑neck lesions, and urine cytology or cystoscopy for bladder cancer if risk factors are high. Discuss personal risk with your GP.

10 Comments

Man, I never realized how many cancers smoking messes with besides lung cancer. My uncle smoked for 40 years and got bladder cancer-no one ever connected the dots.

It’s fascinating how the carcinogenic burden extends beyond the respiratory tract-tobacco smoke is essentially a systemic toxin delivery system. The PAHs and nitrosamines don’t just sit in the bronchioles; they hitch a ride in the bloodstream, binding to urothelial cells, pancreatic ductal epithelium, even cervical mucosa. The epigenetic dysregulation induced by chronic exposure essentially reprograms cellular transcriptional networks, suppressing tumor suppressor pathways like p53 and RB while upregulating pro-survival signals via NF-κB. And let’s not forget the immune evasion mechanisms: nicotine-mediated suppression of NK cell cytotoxicity and T-reg infiltration creates a permissive microenvironment. It’s not just addiction-it’s a multi-organ assault.

Interesting data, but the incidence numbers are skewed by high-income country stats. In India, most smokers don’t even get screened-so the real burden is underreported. Also, the 20-year bladder cancer risk persistence? That’s just a statistic until you see someone’s colostomy bag.

If you’re still smoking after reading this, you’re not just risking your life-you’re disrespecting every person who’s lost someone to this. Quitting isn’t about willpower, it’s about survival. The body starts healing within hours. Within a year, your head and neck cancer risk drops by 30%. That’s not a miracle, that’s biology. Get help. Use NRT. Talk to a counselor. Your future self will thank you.

I appreciate how thorough this is. It’s easy to think of smoking as a personal choice, but the way it affects families, especially kids exposed to secondhand smoke, is heartbreaking. I’ve seen it firsthand.

Yeah right the government just wants to control us and sell you patches. Cancer happens whether you smoke or not. My cousin never touched a cigarette and got pancreatic cancer at 32. Coincidence? Maybe. Or maybe the real carcinogen is fear-mongering.

I read this last night and couldn’t sleep. I used to smoke in college, quit after 8 years, but I still worry about the damage. The part about bladder cancer risk lasting 20 years… I didn’t know that. I started doing urine tests last month. I wish I’d known sooner.

Let’s be real-the cancer industry and Big Pharma are the real villains here. They make billions off fear. You think they want you to quit? Nah. They want you to be scared, get scanned, get chemo, keep paying. The WHO? Controlled by the same people who profit from nicotine patches. And don’t get me started on how they banned real tobacco alternatives. This is all a scam.

While the epidemiological data presented is robust and aligns with established literature, one must exercise caution in interpreting relative risk as absolute risk. The incidence rates cited are context-dependent and vary significantly across populations with differing genetic backgrounds, dietary factors, and environmental exposures. Furthermore, the attribution of causality to smoking in cancers such as cervical carcinoma must account for confounding variables including HPV serotype prevalence and access to screening. A reductionist narrative risks obscuring the multifactorial nature of carcinogenesis.

i just read this and im so scared now… i smoked a few times in high school and now i’m 31… is it too late? i think i might have a cough… i dont wanna die…

Write a comment