Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that inflames the colon and rectum. While most people think of abdominal pain, bloody stools and urgency, there’s a hidden side that shows up on the skin. If you’ve ever wondered why an ulcerative colitis flare can bring a rash or painful nodules, you’re not alone - many patients report skin symptoms before their gut feels the worst.

In this guide we’ll unpack the biology, list the most common skin conditions, explain why they appear, and share practical steps to manage them. By the end you’ll be able to spot early warning signs, talk confidently with your gastroenterologist, and choose the right treatment mix for both gut and skin.

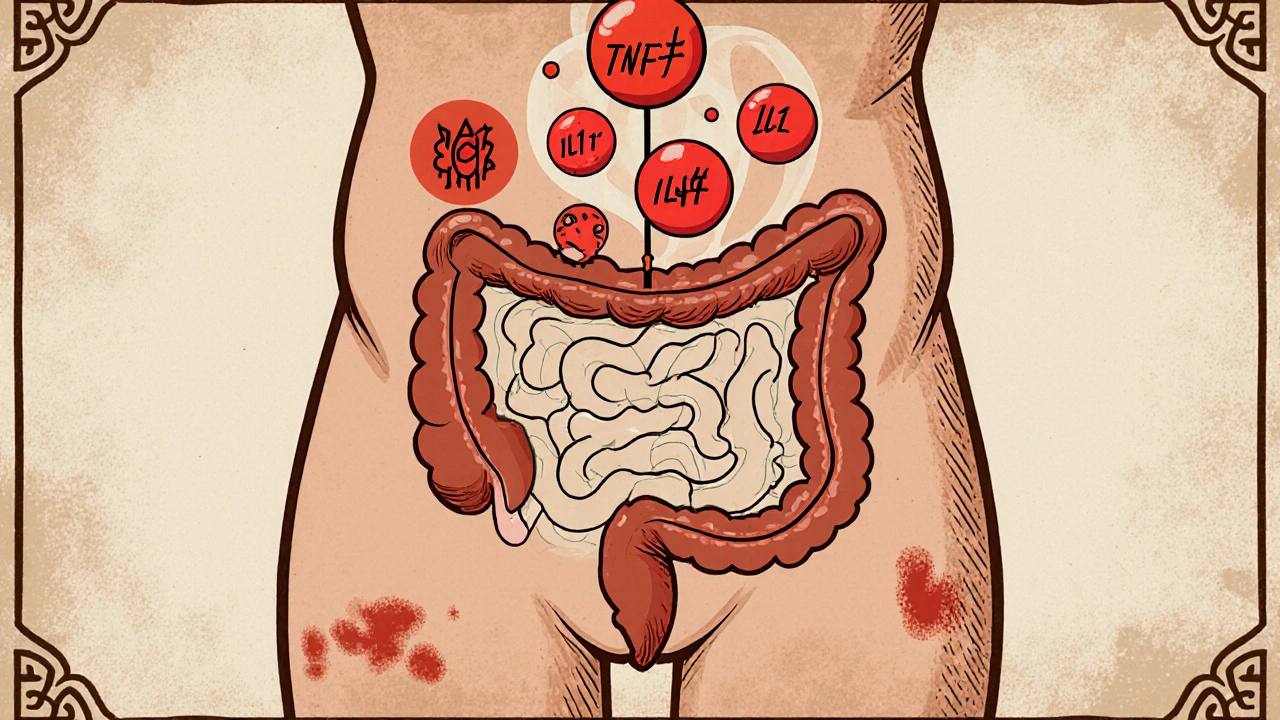

Why the Gut and Skin Talk to Each Other

The gut and skin belong to the same embryonic layer - the ectoderm - and share a lot of immune machinery. When ulcerative colitis flares, cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor‑α (TNF‑α), interleukin‑1β (IL‑1β) and interleukin‑6 (IL‑6) surge into the bloodstream. These inflammatory messengers don’t stop at the colon; they travel systemically and can trigger skin inflammation.

Two key mechanisms link ulcerative colitis to skin problems:

- Immune cross‑reactivity: Antibodies aimed at gut bacteria sometimes mistake skin proteins for foreign invaders, leading to auto‑immune skin lesions.

- Microbial translocation: A leaky gut lets bacterial fragments slip into circulation, prompting a defensive skin response.

Genetics also play a role. Certain HLA‑DQ alleles increase risk for both ulcerative colitis and specific dermatologic disorders, suggesting a shared genetic susceptibility.

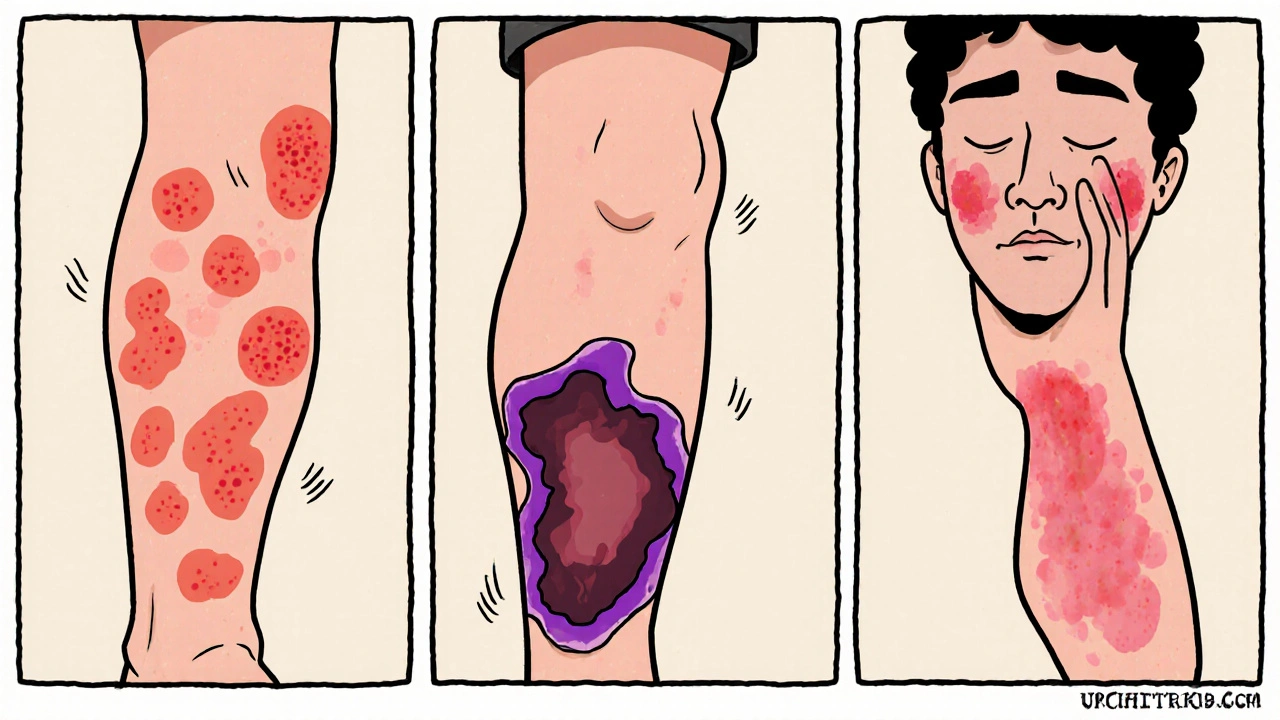

Common Skin Manifestations in Ulcerative Colitis

Not every rash means ulcerative colitis, but a handful of skin conditions show up far more often in IBD patients. Below is a quick snapshot, followed by a deeper dive into each.

| Condition | Typical appearance | Onset relative to gut flare | Common treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythema nodosum | Tender red nodules, usually on shins | Often concurrent with or shortly after flare | Systemic steroids, colchicine |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Rapidly enlarging ulcers with purple borders | Can precede GI symptoms by weeks | Biologics (anti‑TNF), tacrolimus |

| Sweet’s syndrome | Feverish painful plaques on arms/face | Usually during active inflammation | Systemic steroids, dapsone |

| Aphthous‑like oral ulcers | Small white‑yellow ulcers with red halo | Often mirror colon inflammation | Topical steroids, sucralfate |

| Vitiligo‑type depigmentation | Irregular white patches, often on hands | May develop years after diagnosis | Topical calcineurin inhibitors, phototherapy |

Erythema Nodosum: The Red Nodules on Your Shins

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a classic extra‑intestinal manifestation, affecting roughly 3‑10 % of ulcerative colitis patients. The nodules are usually painful, raised, and feel like firm beans under the skin. They tend to appear on the anterior tibial surface, but can show up on arms or torso.

EN often flares in tandem with gut inflammation, making it a useful visual cue that your disease is active. Blood tests typically reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C‑reactive protein (CRP), confirming systemic inflammation.

First‑line treatment is a short course of oral prednisone (0.5 mg/kg for 2-4 weeks) until the nodules soften. For milder cases, potassium iodide or colchicine can be effective alternatives. Importantly, controlling the underlying ulcerative colitis with 5‑ASA agents or biologics often reduces EN recurrence.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum: When Skin Ulcers Feel Like a Nightmare

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is the most feared skin complication because the ulcers can progress quickly and are notoriously painful. About 5 % of ulcerative colitis patients develop PG at some point, and the lesions can appear on the legs, abdomen, or even surgical scars.

The pathogenesis involves neutrophil dysfunction and an overactive IL‑1/IL‑17 axis. A key clinical tip: a seemingly harmless bump that turns into an expanding ulcer after a minor trauma is often a sign of pathergy, a hallmark of PG.

Treatment starts with systemic immunosuppression. Anti‑TNF agents like infliximab have shown remission rates above 70 % in controlled trials. For patients who cannot tolerate biologics, cyclosporine or tacrolimus ointment offers an alternative. Wound care is essential - gentle debridement, non‑adhesive dressings, and pain control with opioid‑sparing regimens.

Sweet’s Syndrome and Other Acute Dermatoses

Sweet’s syndrome, also called acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, presents with sudden, tender, red plaques often on the face, neck, and upper extremities. Fever and neutrophilia accompany the skin findings in roughly 30 % of ulcerative colitis cases displaying this pattern.

Unlike PG, Sweet’s lesions are more superficial and respond dramatically to a short steroid burst (prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg for 7‑10 days). For recurrent episodes, dapsone or colchicine can keep the rash at bay.

Oral Aphthous Ulcers: The Mouth Mirrors the Colon

Small, painful mouth ulcers are often the first sign that an ulcerative colitis flare is brewing. They tend to appear in the anterior oral cavity, and the number of ulcers often correlates with disease activity measured by the Mayo score.

Topical interventions such as sucralfate swabs, triamcinolone dental paste, or even honey dressings can speed healing. In persistent cases, a short systemic steroid taper or an increase in 5‑ASA dosage may be warranted.

Vitiligo‑Like Depigmentation: When Color Fades

Vitiligo is not as common as EN or PG, but about 1‑2 % of ulcerative colitis patients report new depigmented patches. The loss of melanocytes is thought to stem from an autoimmune attack that targets both gut epithelium and skin pigment cells.

Early referral to a dermatologist is key. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus 0.1 % ointment) combined with narrow‑band UVB phototherapy can restore pigment in many cases. Addressing the underlying gut inflammation with biologics may also halt progression.

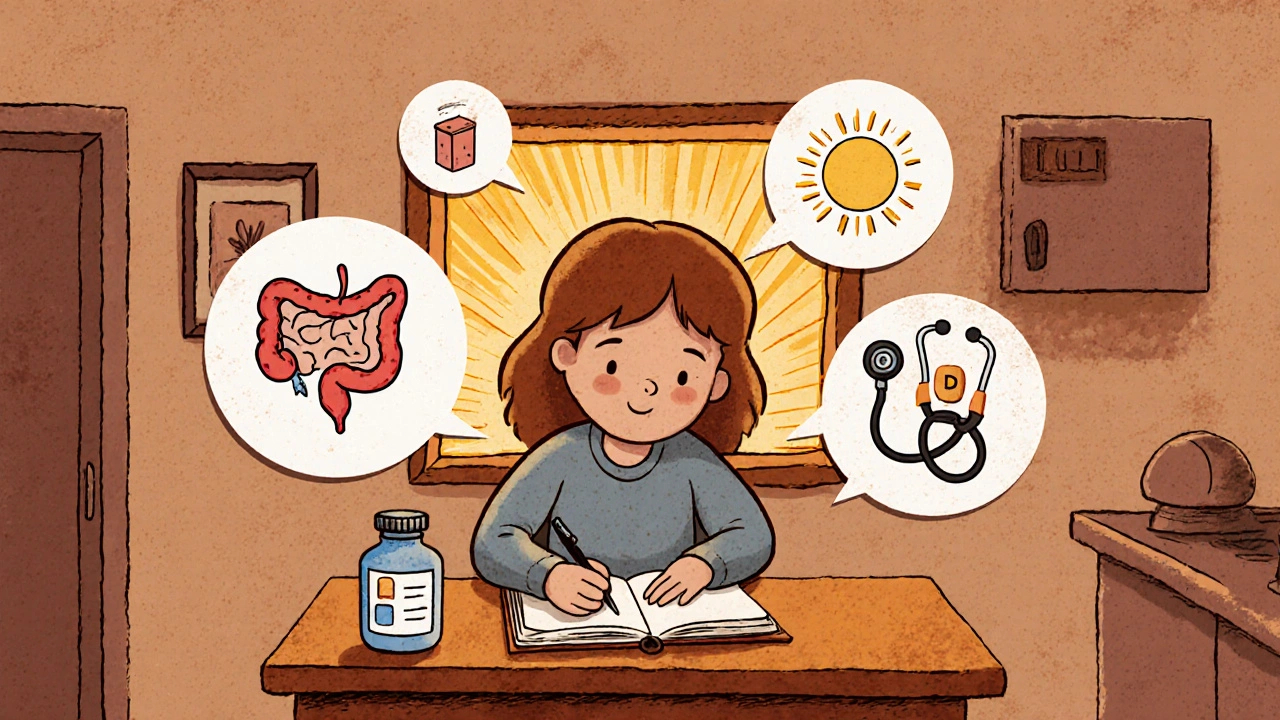

Practical Steps to Manage Skin Issues When You Have Ulcerative Colitis

- Track symptoms holistically. Keep a simple diary noting bowel habits, stool blood, and any skin changes. Patterns often emerge that help your care team adjust treatment before a full‑blown flare.

- Communicate with both gastroenterologist and dermatologist. Share the diary, lab results (CRP, ESR), and medication list. Dual‑specialist coordination is vital for conditions like PG, where systemic therapy overlaps.

- Don’t self‑medicate with over‑the‑counter creams for ulcerative colitis‑related rashes. Many OTC steroids can mask symptoms and delay proper diagnosis.

- Consider early biologic therapy. If you have recurrent EN, PG, or Sweet’s syndrome, anti‑TNF or anti‑IL‑12/23 agents have dual benefits for gut and skin.

- Maintain skin hygiene. Use fragrance‑free moisturizers, avoid tight clothing on the shins, and protect wounds with non‑adhesive dressings.

- Watch nutrition. Deficiencies in zinc, vitamin D, and B12 can worsen skin healing. Supplements should be guided by blood tests.

- Plan for stress management. Stress spikes cytokine release, which can aggravate both ulcerative colitis and skin inflammation. Mind‑body practices (yoga, meditation) have shown modest reductions in CRP.

When you combine these steps with a personalized medication plan, most patients see a marked reduction in skin flare frequency and severity.

Key Takeaways

- The gut and skin share immune pathways; flare‑ups in ulcerative colitis often trigger skin inflammation.

- Common skin manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome, oral aphthous ulcers, and vitiligo‑like depigmentation.

- Systemic treatments that control ulcerative colitis (e.g., anti‑TNF biologics) usually improve skin symptoms, too.

- Early detection via symptom diaries and coordinated care between gastroenterology and dermatology leads to faster relief.

- Holistic lifestyle choices-nutrition, stress management, and skin care-play a supporting role in keeping both gut and skin healthy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can skin problems be the first sign of ulcerative colitis?

Yes. Conditions like pyoderma gangrenosum or oral aphthous ulcers can appear weeks before noticeable bowel symptoms. If you notice a painful, rapidly spreading ulcer on your leg, it’s worth discussing with a doctor, especially if you have a family history of IBD.

Do over‑the‑counter steroid creams help?

They may provide temporary relief for mild erythema nodosum, but they won’t treat the underlying inflammation. Relying on OTC steroids can delay proper systemic therapy and worsen the ulcerative colitis flare.

Is it safe to combine biologics for gut and skin?

Biologics such as infliximab or adalimumab target the same inflammatory pathways in both organs, so they are often the preferred choice when skin lesions are severe. Your specialist will monitor infection risk and adjust dosing as needed.

Are there lifestyle changes that reduce skin flares?

A balanced diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, adequate vitamin D, and low refined sugar can dampen systemic inflammation. Regular gentle exercise improves circulation, and stress‑reduction techniques lower cytokine spikes that trigger skin lesions.

When should I see a dermatologist?

If a rash is painful, rapidly enlarging, or doesn’t improve within a week of standard ulcerative colitis therapy, schedule a dermatologist visit. Early biopsy and targeted treatment can prevent complications, especially with pyoderma gangrenosum.

Understanding the link between ulcerative colitis skin conditions empowers you to catch problems early, work hand‑in‑hand with your clinicians, and choose treatments that hit both the gut and the skin. Stay proactive, keep notes, and don’t hesitate to ask for a dermatology referral when you notice something new on your skin.

9 Comments

They don’t want you to see the full picture; the pharmaceutical giants have perfected a secret handshake that trades skin flare‑ups for higher prescription volumes, all while the media sings praises for the latest biologic miracle.

While the narrative can feel conspiratorial, the data support a mechanistic link: TNF‑α blockade mitigates both mucosal ulceration and neutrophilic dermatoses, so integrating anti‑TNF agents into a treat‑to‑target strategy can harmonize gut and cutaneous outcomes.

Erythema nodosum signals systemic inflammation, treat promptly.

When you chart the timeline of a flare, the skin often lights up before the colon even whispers its distress, making dermatologic vigilance a frontline diagnostic tool. The cascade begins with microbial translocation: a compromised epithelial barrier permits lipopolysaccharide fragments to flood the bloodstream, hijacking pattern‑recognition receptors on dermal fibroblasts. Those receptors unleash a torrent of interleukins that recruit neutrophils, the same cells that pave the way for pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Simultaneously, auto‑antibodies generated against gut bacteria cross‑react with cutaneous antigens, creating immune complexes that lodge in the sub‑dermal matrix. Genetics rarely sit idle; HLA‑DQ variants have been mapped to both ulcerative colitis susceptibility and increased risk for erythema nodosum. Nutrition plays a covert yet pivotal role: omega‑3 fatty acids compete with arachidonic acid, dampening the eicosanoid surge that fuels both gut and skin inflammation. Vitamin D deficiency, common in IBD due to malabsorption, removes a crucial immunomodulatory brake, permitting unchecked cytokine release. Stress, often dismissed as a psychosomatic footnote, actually amplifies cortisol‑driven cytokine production, accelerating the skin‑gut feedback loop. The therapeutic implication is crystal clear: systemic control of inflammation with agents such as infliximab or ustekinumab often yields rapid remission of skin lesions. Topical measures remain adjunctive; non‑adhesive dressings and fragrance‑free moisturizers reduce secondary irritation and support barrier recovery. Early dermatology referral cannot be overstated-biopsy, culture, and specialized wound care cut down morbidity. Patient‑reported outcome measures that capture both stool frequency and rash severity provide a more holistic assessment of disease activity. In practice, I counsel patients to log any new plaques, nodules, or oral ulcers alongside their bowel diary, creating a symptom matrix that guides therapeutic escalation. Moreover, interdisciplinary case conferences between gastroenterologists and dermatologists foster a unified treatment algorithm, preventing fragmented care. Finally, remember that remission is a shared journey; adherence to medication, balanced diet, and mindful stress‑reduction techniques together keep the gut‑skin axis in equilibrium.

Seeing the gut and skin as partners reminds us that health is a tapestry, each thread affecting the whole.

I appreciate the perspective; coordinating care with a dermatologist early can indeed prevent complications and streamline treatment decisions.

It’s astonishing how many patients dismiss early skin signs as mere irritation, only to later endure severe ulcerative colitis complications that could have been mitigated with prompt attention.

Living with those hidden eruptions feels like a silent alarm that nobody hears until the pain becomes unbearable, and the frustration builds with each missed appointment.

In the end, neglecting the skin is just another way of ignoring the body’s own philosophy of balance.

Write a comment